Styron as young literary lion You can’t count me as any kind of Pollyanna. Give me a few overcast days in midwinter, a riff of Miles’s horn on the radio, and I’ll turn blue with the best of them. But melancholy can be a pose, a romantic notion that the tragic is always more interesting than the comic, the mistake too many younger and serious writers tend to make. I’ve been mulling over melancholia lately while reading William Styron. With the recent arrival of Styron’s Selected Letters, I’ve been re-reading his 1951 debut “Lie Down in Darkness” – a bestseller that propelled the 25-year-old writer into instant celebrity. Soon he was padding around the literary lion’s den with the likes of Mailer and James Jones and other red-blooded he-men writers of the Great American Novel. Styron eschewed what he called the “Hemingway mumble school,” tending more toward the purplish expanses of his fellow Southerner Thomas Wolfe. “When I mature and broaden, I expect to use language on as exalted and elevated a level as I can,” the young Styron wrote his Duke mentor William Blackburn. "I believe that a writer should accommodate language to his own peculiar personality and mine wants to use great words, evocative words, when the situation demands them.” I hadn’t read Styron’s novel in 35 years, not since I breezed through as a junior in a contemporary American Lit survey in college. In my bifocaled hindsight now, Styron’s book reads like a young man’s overly romantic vision, not of the Good Life, but of the Marriage Gone Bad – the sorry saga of the alcoholic lawyer Milton Loftis, his estranged Southern belle of a wife, Helen, and their two daughters, the impetuous Peyton, and the special needs daughter, Maudie. The novel charts a single day in August, 1945, just weeks after the bomb feel on Hiroshima. Peyton has committed suicide in New York, and her body had been borne back by train to to the fictional Port Warwick in Tidewater Virginia. Over seven sections and 400 pages in my water-damaged Signet paperback, the book follows Loftis and Helen’s separate journeys to the cemetery, and through their back story of their sad marriage. The opening is masterful, putting “you” into the steamy Southern landscape as the train pulls into the fictional Port Warwick. Throughout, Stryon has a muscular omniscient point of view that can see a fly land on a fat man’s face or how female golfers have to tug at cinching panties, an authoritative voice we don’t hear too often in our more ironic times with the nebbish narratives that have followed after David Foster Wallace. Stryon labored mightily over the book, complaining in his letters how agonizingly slow he found writing. Unfortunately, it shows in the books, which becomes a long march through gloom, leavened by very little humor. There’s a reason that Shakespeare has a jester in King Lear, for a little comic relief and to add to the absurdity. Styron’s idea of comedy is sarcastic, picking on the wide-eyed Negro stereotypes of the time. In the Jim Crow era, pre-Civil Rights South before airconditioning and television, Styron unveils a benighted look at the prevailing racist attitudes. It’s not pretty to read. But it’s still a young man’s notion of tragedy that turns his book into melodrama, the scenes slow to the pace of sticky molasses. There’s pathetic fallacy aplenty as the landscape echoes the alcoholic mood swings of Loftis or the high strung neuroses of Helen, and too often, Styron’s swagger wades too deep into the purplish patches that tripped up Thomas Wolfe. In the end, I had to lay down “Lie Down in Darkness.” I don’t think too many readers will be taking that novel up, nor his “Confessions of Nat Turner” or even “Sophie’s Choice.” Styron himself admitted that his latter fame probably depended more on his slender memoir, “Darkness Visible” about his courageous battle against a debilitating chronic depression, than on his fatter, darker fictions. Styron reads now like a boy whistling in the dark, trying to keep his spirits up, but afraid to truly play. I’m not arguing for sweetness and light, but that a maturer vision sees how to balance the light and the dark in any artful composition. I hold to what one of my teachers, Allan Gurganus, always insisted on: that humor and horror must go hand in hand, hopefully, in a single sentence. Mac McIlvoy suggested in one of his topnotch workshops that writers have to learn to “play in the dark.”

2 Comments

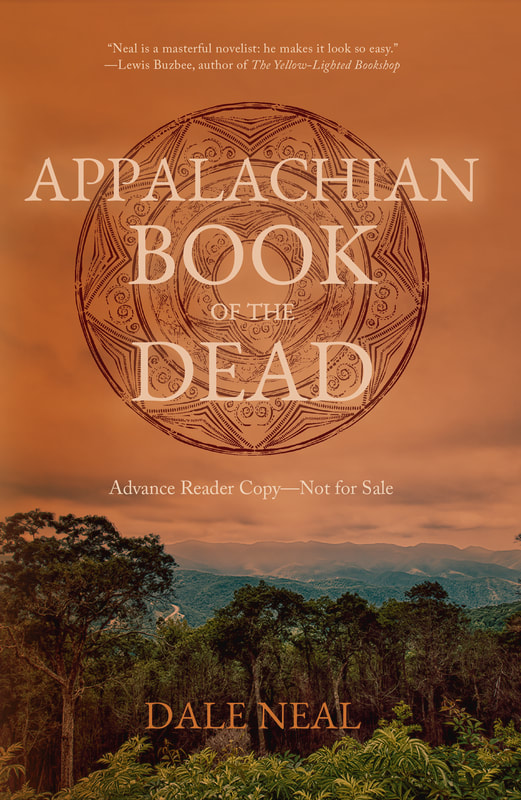

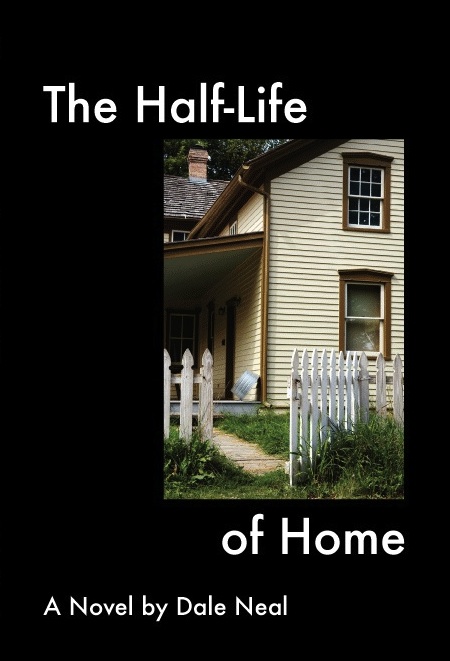

James Dickey, author and actor Faulkner was talking of the South of course when he wrote “the past is not dead, it’s not even past.” Hell, the dead don’t stay buried in these parts, not even if you try to drown them. I was reminded of that the other night, flicking through the HD hinterlands of TV cable when I came across John Boormann’s 1972 thriller “Deliverance.” Even if you never saw the Burt Reynolds-Jon Voight movie, you’ve heard the iconic soundtrack music, “Dueling Banjos” originally written by Arthur Smith (though he had to sue to get his name recognized, but that’s a whole ‘nother tale.) Poet turned novelist James Dickey did no favors to Appalachian natives in his bestseller with its depiction of “the Country of Nine-Fingered Men,” a dark land of sadistic hillbillies eager to sodomize Atlanta suburbanites out for a weekend adventure. Dickey tapped into a deep distrust and terror of residents living in the shadows of mountains. The Other is the toothless man living in the holler with an outhouse and a still up on the ridge. Decades after that movie was filmed in Rabun County, Ga., and over in Sylva, N.C. you still see the bumper stickers “Paddle faster, I hear banjo music.” But the scene that lingered for me showed graves being dug up on the banks of the river slowly flooding to form a reservoir to power Atlanta’s urban sprawl. That scene was actually filmed, not in Georgia, but in South Carolina at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church cemetery which now lies 130 feet beneath Lake Jocasse. We’ve been relocating cemeteries forever in these parts. Folks over in Swain County still grow furious over the “Road to Nowhere” promised by the government, but which never materialized after Lake Fontana flooded their small towns and family farms in the 1940s. The story was repeated across the Southern Appalachians where the TVA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built hundreds of dams, dislocating plenty of families and often covered the graves of their ancestors with waters much more than five fathoms deep. So it comes as no surprise how often floods and forgotten graves show up in Southern fiction. The theme runs like a dark current through the reigning Appalachian master Ron Rash’s work, from his first novel, “One foot in Eden” and “Saints by the River” also based around Lake Jocasse in South Carolina, and in his current novel, “The Cove” where a TVA surveyor goes missing in a haunted holler slated for a lake. Those lakes were built to provide electricity to growing cities and their suburbs whether in Charlotte or Greenville, S.C., or down to Atlanta, but the progress of rural electrification or air conditioning never comes without its own cost when we drown the last wilderness and pieces of our past. An image of a relocated cemetery haunted my imagination and inspired me to write my novel “The Half-Life of Home,” I saw in my mind’s eye a picture of men digging up a graveyard, coffins swinging up into the air in an artificial resurrection. The thirst for electricity, for suburban power was the culprit here, but not in hydroelectric dam, but in a nuclear repository. Since dams sprang up across the South, we’ve also added the strange cones and domes of nuclear plants across the region, with their irradiating wastes with deadly half-lives spanning millennia. A remote cove in my neck of the woods actually came under consideration in the late 1980s as a potential radioactive reservation where East Coast’s stores of spent nuclear rods could be buried for ten thousand years. As a cub reporter I covered those heated public meetings where I heard a white-haired native warn that the region had already seen two forced migrations: the Trail of Tears and the TVA removals. The feds would be chasing other folks off their homesteads in the name once again of national progress. Fortunately, that mad scientist-hatched idea died. We still have nuclear waste to contend with, but at least we’re not burying it in my backyard. Yet the seed was planted in my imagination. Men in moon suits digging up generations of graves. What if… what if? Jesus said let the dead bury the dead, but it seems like the Southern writer’s morbid duty or at least his inclination is to keep pawing away at what’s been covered over, conveniently forgotten. We can’t let the bones rest, the skeletons in the closet. We are always like Hamlet hopping down in the hole, eyeing Yorick’s skull raised in our palm for the audience’s appreciation. And in that sense, Faulkner was right. We breathe life into the past, put flesh on fossils, when we blow away the dirt of the grave or dive deep into the dark waters covering the beds of lakes and forgotten farms. Literature is too often about seemingly unbearable loss, but writing is a way of making sure nothing is ever forgotten. |

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed