|

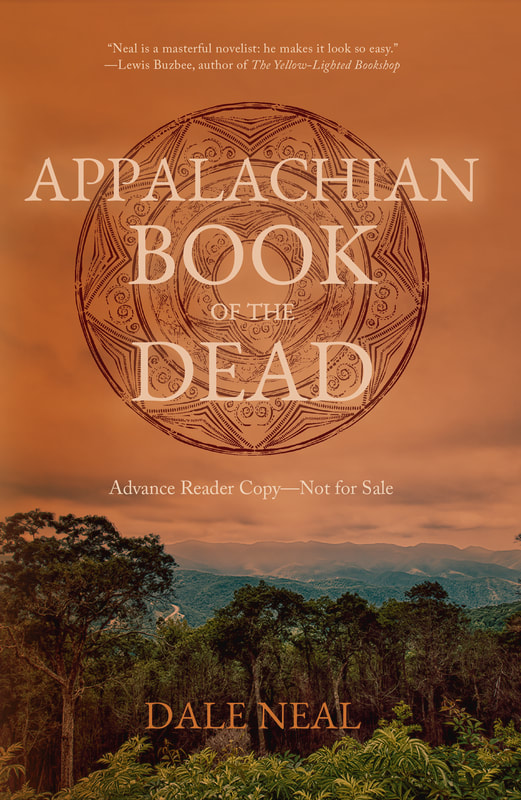

Songwriter Ben de la Cour serves up a gritty Southern Gothic Americana in his eerie songs, and so it seems natural that he might be drawn to the themes of my novel "Appalachian Book of the Dead."

The Nashville-based musician has just released his new album "Sweet Anehedonia" with the hit single "Appalachian Book of the Dead." Let me let Ben explain in an interview with the British website Folk Radio: "I remember first hearing the phrase "Appalachian Book of the Dead" a long time ago in reference to a poem that I later found out was written by Charles Wright. I think I had it filed away subconsciously for years until Shari Smith at Working Title Farm contacted me with this idea she had about pairing authors and songwriters together on a project and somehow I ended up being paired with Dale Neal who wrote a novel called... "Appalachian Book of the Dead". So I started working on the song before reading the book, then I read the book and loved it and as soon as I finished it I was able to fill in the few blanks left in the song and it kind of came together in full. "The song is definitely inspired in part by the book but it's mostly my attempt at capturing the feeling I always get driving through North Carolina and East Tennessee late at night. "I always loved the quote by Poe, "The best stories are an arabesque of supernatural menace and wry jesting". This is my feeble attempt at doing justice to that."

9 Comments

From the award-winning author of APPALACHIAN BOOK OF THE DEAD, Dale Neal’s KINGS OF COWEETSEE, an Appalachian community faces a reckoning when a missing ballot box from a historic election resurfaces with new clues to old corruptions, crimes, and coverups." Birdie Barker Price, a former schoolteacher and recent widow, heads the Coweetsee County Historical Society, located in the old jail in the remote mountain county. She is the keeper of county history and loves to sing old murder ballads she learned from her great Aunt Zip. She’s grieving the loss of her second husband, Talmadge Price, who documented the county’s many barns before he got cancer. She discovers a mysterious box left on her porch – a ballot box that was never counted in the contested 1982 election. Maurice Posey had won 30 years ago and served unopposed as the county’s sheriff until he was convicted on federal vote-buying charges. Birdie seeks the advice of her first husband, Roy Barker, one of Posey’s former deputies, who is running against an incumbent and outsider Frank Cancro, who was appointed to fill out the disgraced Posey’s term. Roy still carries a torch for Birdie, who ran off with the hippie newcomer Talmadge. He hopes in becoming sheriff, he can reclaim the county’s past and his purpose. Birdie also frets about Charlie Clyde Harmon, a convicted felon, who has returned to town after a lengthy sentence for arson at a Black church in which a deacon died. Charlie Clyde maintains his innocence, insisting he was framed . Birdie’s friend, Shawanda Tomes, an African American quilter, is a faithful member of the church that has since been rebuilt on a million-dollar insurance policy, but she finds it impossible to forgive Charlie Clyde for his crimes. As a teenager, Harmon intentionally ran over a drunk in the road. To get him off on a lighter juvenile record, his aging parents sent his two younger sisters to be “married” to the county’s powerbrokers. Deana and Rhonda Harmon later returned home, scarred by their experience, and forever haunted by the local gossip. Rhonda became a wild party girl with many lovers, and gave birth to a daughter, but she never revealed the daddy’s identity. Rhonda’s body was found in the river, ruled a suicide by Posey. The novel builds toward the November election and a crucial fundraising event that gathers all the county’s characters, leading to revelations about hidden crimes. The women who have suffered and sang ballads about their woes begin to take their revenge against the supposed Kings of the county.  Fifty years after I first found my entrance into real literature, in “a stone, a leaf, an unfound door” – that plaintive cry in Thomas Wolfe’s debut novel “Look Homeward Angel, I’m still wrestling with Mr. Wolfe. Wolfe was my first literary love and I devoured his first novel, and his last, posthumous tome – “You Can’t go Home Again.” By then, even at 16, I was noticing Tom had a habit of repetition, and the avalanche of ambition and floodwaters of feeling were, well, a bit much. It’s October and it’s always Tom’s month, the season that he worshipped in words. I recently picked up “Of Time and the River,” the sequel to Eugene Gant’s journey started in “Look Homeward, Angel.” Time of course hasn’t been kind to poor Tom’s reputation. Even in his celebrated but short lifetime, he got an earful from the critics about his rhetorical excesses, his appetite and ambition to fit all of America and Life into his one super book. Though Faulkner thought his compatriot the most talented writer of their celebrated generation, for his failure. To use a metaphor of baseball, a game Tom adored, he was always trying to swing for the fences and often struck out mightily. So I wanted to see how Tom had failed and how he had succeeded. At 800-plus pages, I’m probably not going to plow through the whole of “Of Time and the River,” and Eugene’s constant yelping of “goat-cries.” But I’m pleased to see the true gems that surface in the powerful currents rushing through this novel. When Wolfe finds the sweet spot, he is a great writer, not so much in what Eugene is thinking, but in the close descriptions of his family, Helen and Eliza and W.O. Gant back in Altamont. Just as Ben’s death from the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic is the high point of “Look Homeward, Angel,” Tom hits home again in the death of his father. He’s a master of the deathbed scene, and his description of W.O.’s demise from a long cancer is harrowing. What struck me is the dream sequence W.O. has on his deathbed, going back to the Pennsylvania countryside of his blighted youth. He meets a mentally challenged neighbor who comes rushing from his house in greeting. Gant gives him a plug of apple-chewing tobacco and goes on his way through a sad and darkening woods. It’s a haunting dream, shorn of some of Wolfe’s triad of adjectives. What’s truly touching is the forgiveness, the softness of a bad and broken marriage still bound together at the end, when Gant speaks his wife’s name, and apologizes. As he lays dying, he sees the child at the door, the child he once had been. Gant starts calling for his father, futile words lost in the hemorrhage, “the lake of jetting blood” from his mouth and nose, the indignity of death, even as he is at peace. That death comes relatively early in the book at page 280, and sets Eugene off on his journey away from home, up north and overseas, in search again of his own mythic father figure. This was Wolfe’s wild dream, to go out and bring the whole world back home with him. It wasn’t always a graceful affair. Wolfe can nail a perfect metaphor, then go on to belabor his point for pages. He’s trying to articulate the ineffable, and for that, I think Faulkner rightly recognized his talent and his spectacular failure. I don’t know many writers who still read Wolfe for craft or for tips on writing tidy novels, but I’m impressed by how many writers first fell in love with literature through Wolfe’s zealousness. Wolfe was the one who found the unfound door and was banging with all his might, with all his words, with all of his obsessed and tortured soul, trying to say what was on the other side.  During these pandemic times, shut up in the house with too much time on my hands, in search of what we’ve lost now, I’ve found myself in the sway of Literature’s great timekeeper, Marcel Proust. Over the past year or so, even before the lockdowns and our uneasy economic re-openings, I’ve been delving into the seven volumes of A la recherche du temps perdu, or In Search of Lost Time. I’m in good company. I’ve always remembered the novelist and Civil War scholar Shelby Foote, who rewarded himself by rereading Proust after finishing up one of his own books. I’ve been dipping into favorite scenes, and yes, skipping over some of the more endlessly plodding passages on the mores of a lost world and society from a century ago. Proust can be ponderous, and reading him can sounds precious if not pretentious, an effort of the ego like climbing Mt. Everest. Look at me and what I’m reading. His madeleines of involuntary memory aside, Proust is not everyone’s cup of tea. I found him boring when I first tried tackling Swann’s Way. I found the volume shelved high in the high-windowed, oak-paneled library of R.J. Reynolds High School in my native Winston-Salem, eons and an ocean away from Proust’s Paris. Like so many bookish adolescents, I dreamed of becoming a writer. I knew that Proust and Joyce and Faulkner were all heavyweights I would have to contend with, but I simply couldn’t get into the Narrator’s struggle as a young boy to go to sleep. Not much in the way of plot. I was getting sleepy myself in those rambling sentences. I closed the book and wouldn’t attempt Proust again for another 25 years. You have to be older perhaps to appreciate Proust’s deft handling of time, particularly how we age past our previous selves. Proust, I’ve discovered, provides a way, a path to reclaiming your previous lives, to rediscovering previous versions of yourself. In his way, Proust is literature’s great ophthalmologist, concerned with the fleeting inner visions, the sudden insights, helping us to see ourselves and our worlds more clearly. Proust polishes up for us a new pair of spectacles. We slip them on and the details of our world comes into brilliant, searing, beautiful focus. “In reality, every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self. The writer’s work is merely a kind of optical instrument which he offers to the reader to enable him to discern what, without this book, he would never have perceived in himself. … He must leave the reader all possibly liberty, saying to him: ‘Look for yourself and try whether you see better with this lens or that one or this other one.’” Reading Proust reminds us of our previous reading selves, the experience of reading itself. I was in my 40s. Proust’s words make me pause. I find myself staring out the window after a page or so of his sinuous sentences, how he works his way into seeing. I see myself looking out the window. Lost in thought, I wasn’t paying attention to our puppy hound dog who ate the corner of one of my wife’s keepsakes, a needlework pillow showing a curly-haired girl in a white dress, something you would find in the parlor of Odette as Swann’s wife. My wife was furious with me, and exacted her revenge. Later she took one of my volumes of Proust from the shelf, ripped out a random page, then reshelved the book. I would discover the damage in another rereading. In all the pages of Proust, not a lot of things actually happen plot-wise. My angered spouse had by chance taken out the page where the Narrator’s grandmother actually dies. That scene now etched in my own life, that lacuna, that lost memory. Proust captures how we stumble into insight, transported into a whole life by the taste of a cookie we used to savor as a child, or the smell of hawthorn blossoms, the perfume of young romance, the instant how we fall in love with an idea, the glimpse of our own Helen of troy, the world’s most beautiful woman, disguised as a simple peasant girl with milk buckets beside a train. I went to Paris, with Proust in mind. Toured the Champs Elysee, seeing in my mind’s eye where Marcel chased after his first love Gilberte. In the Musee Carnavalet in Paris, I paused by the writer’s bed with its rich blue satiny spread and a nightstand with one of the notebooks, the same furniture where he had lay as an invalid in the cork-lined room, continually adding to his masterpiece with his pen, scrap of paper after paper, elaborating, weaving a richer tapestry like the Arabian Nights he was so fond of. Here was where the magic was made in rumpled bedsheets. I could almost see the languid form of the man himself, the impression on the mattress and sheets. We ate Monte Blanc at Angelina on Rue Rivoli whipped hazelnut confection, at the same tea room, frequented by Proust. The taste of the rich chocolaty dreamlike. Inimitable. We came back the next day and ordered it again. And of course, we made our way to the cemetery at Pere Lachaise, that city of the famous dead where Colette, Gertrude Stein, Alice Toklas, Oscar Wilde, Jim Morrison and my hero, Proust, rest for all eternity. I ran my finger into his engraved name on the reflective granite slab that shows my dim face. Time does not move in straight progressive lines we like to think, but in strange circles. In Time Regained, I started reading faster, coming at last to the end, the final pages in which Proust had been preparing us for more than 1,000 pages. The taste of the madeleine cookie, the sight of the steeples in Martinsville, the uneven cobble stones in the drive that remind him of Venice, the starchy touch of the linen napkin to his lips. Finally, the bell that still sounds at the garden gate of his childhood as Swann finally left that long-ago evening Marcel kept waiting for his mother to come kiss him. He sees his life as a series of jewels that he can recapture as a writer. Art is life rescued from Time. Marcel who has spent volumes in search of his vocation, wanting to be a writer, but doubtful of his talents, finally gives himself permission to become the Narrator of his own life, writing the book we’ve been reading all along. It is a writer’s story after all, a book that would shape writers to follow, that impulse to turn life into art. “And I go home having lost her love. And write this book.” Jack Kerouac would write a few decades the final lines of The Subterraneans, one of my all-time favorite endings. Old Jack tips his hipster hat to the French genius with more than a little American swagger. “My work comprises one vast book like Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past,” Kerouac admitted, “except that my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterwards in a sick bed.” Proust is more of a grown-up in the end than Kerouac, both of whom died early deaths but left behind their books. Kerouac still appeals to my inner adolescent, but Proust makes me appreciate aging, that country that the young can never really imagine. Time Regained takes on a bittersweet yet somehow comic tone showing how time robs us of ourselves. In the final pages of the book, the Narrator has returned to Paris after years away in a sanitarium and after the terrible war. He’s back in the swing with a party at the mansion of the Prince Guermantes, the family he had always envied for their social status, their storied name. But everything has changed, the social pecking order has been upended. And everyone the Narrator meets at the party seems weirdly disguised by the terrible effects of Time. Here is the sad, hard truth, we are changing by the moment ourselves, losing our lives each moment to faulty memories. “At every moment of our lives we are surrounded by things and people which once were endowed with a rich emotional signification that they no longer possess. But let us cease to make use of them in an unconscious way, let us try to recall what they once were in our eyes.” In this pandemic, what’s been unavoidable is a lingering grief, a deep sorrow at the world we have lost, the care-free ways of going to restaurants, and concerts and museums, being in crowded sidewalks and subways, the press of human flesh about us. These things may return in time, but the way we experienced our lives only a few short months ago is now lost. Like Proust, I am composing and recapturing the moments of my life, writing myself as I read the passing chapters. The vague dreamlike moments take on solidity like statues, that glimpse of the Winged Victory of Samothrace down the long hall of the Louvre. That frozen moment you see the largeness of life, even as Time flies away. What remains. What lasts. What is never lost. I close the pages of the thick volume and stare out the window at the spring, at the empty streets, at the fleeting times.  The satellites are watching me make my way up a 45-degree incline, tracking a faint trace uphill from Fire’s Creek in the Nantahala Forest. It’s a cool, overcast day with the smell of rain in the air. I’ve driven all morning down from Asheville to Clay County, just north of the small town of Hayesville. There are plenty of trails closer to home, but I wanted to experience this short jaunt, to see for myself what this landscape’s first human inhabitants might have seen, to follow in the footsteps of ghosts and forgotten history. I’ve discovered this trail by happenstance, reading of the ancient Cherokee network of footpaths that crisscrossed the Southern Appalachians. Most of the major trading routes they followed have long since been paved over by modernity and asphalt. Where the tribe once walked, tourists and retirees zip along in SUVs and RVs. But a handful of the untouched, original trails remain, documented by the obsessive Cherokee pathfinder, Lamar Marshall of the Wild South preservation nonprofit. Marshall has made it his mission to travel these old ways. This morning, I’m traveling a 2.5-mile trail that rises some 2,000 feet from the roaring waters of Fires’ Creek to the surrounding ridges under Big Stamp, a former bald where deer and bison had bedded down on the grassy meadow centuries ago. Marshall’s description of the Cherokee trail seems accurate. This does go unerringly in a straight uphill line, unlike the switchbacks of later trails constructed for modern hikers. Cherokee trails were hated by the American armies who penetrated into their mountain kingdom. Their trails go straight up and down the mountains at perilous inclines that make horses balk and hauling wagons impossible. These were the fastest routes to the ridgetops before dropping down to the river towns where the Cherokee raised their children, grew their corn and danced in the ceremonies. This trail would likely have been a route over the ridges between the river towns of Tusquitte near modern-day Hayesville over to Tomatly, just north of Andrews. At half a mile, I’ve climbed about 800 feet, according to the GPS on my watch. The satellites orbiting hundreds of miles overhead watching me like an ant crawl up the mountainside. The trail itself tends to disappear in the leaf litter, a bare hint or suggestion running across roots and rocks. But this ancient route has been maintained. Blue blazes dot the trees above, rectangular plastic strips nailed to the trees every 50 feet or so, and crews have come through with chainsaws, clearing deadfall of previous winters. I follow my own spirit guides, my hiking companions today – Ben my faithful Golden Retriever and a new recruit Merlin, a rescue Poodle who’s about a year and half. Merlin stays by Ben’s side as they travel, Ben stopping ahead to make sure I’m not getting lost as I catch my breath. Ben stops to wallow in the dust, picking up a blazon on his right shoulder of some funky green shit, an irresistible spoor. There are signs of other animals who have followed this same path, scat - long ropy droppings of predators who’ve feasted on white and dark furred prey. Perhaps bear, maybe coyote. Another good sign. The Cherokee like indigenous people worldwide probably followed game trails. As I scramble uphill with labored breath and aching calves, the surrounding mountains come into view through the bare winter woods. At my back there is Brasstown Bald, down in Georgia, and I get glimpses of Lake Chatuge, the impoundment of the Hiwassee River, which flooded out old towns of the Cherokee and the white settlers who came later. There are no signs of civilization other than that diverted water. A jet drives unseen overhead, screeching across the sky, probably on a direct flight path out of Hartsville International 100 miles southwest in Atlanta. It is hard to escape our time and technology. The mountains keep their ancient shape, but the woods would have been different. The old-growth forests were clear-cut a century ago. And the chestnuts that made up a huge part of the hardwood died out with a blight brought from China. The younger growth is scragglier with more underbrush. There are blackened stumps and scorched trunks, signs of the massive wildfires that swept the Nantahalas during a fierce drought two years ago, another red-warning signal of the climate change that is reshaping our hospitable planet. Every landscape spells its own loss. The Cherokee of course were tragically uprooted from their homeland nearly two hundred years ago and forced to march west to Oklahoma along the Trail of Tears in one of our history’s darkest chapters. A few hardy survivors refused the journey, hiding out in the remote coves. These families would become the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Traces of the Cherokee remain, their language merged with the landscape. Any map shows place names from the Cherokee or Tsalagi language: Watauga, Cowee, Cullasaja, Wayah Cartoogechaye, Hiwassee, Nantahala, the list goes on. I have a handful of Cherokee words I’ve learned, though I can’t really follow any fluent speaker. The language itself is more concrete and specific than English, with syntax placing us in time and space before settling on the individual speaker. I’ve learned from a native speaker Bullet Standingdeer who theorizes that the Tsalagi syllables and their piled-up order tell the listener where to physically look. Instead of placing the ego as subject first in your sentence, it’s a different way of walking through a welcoming world, Nogwo usdi nvnohi gega. Now the small road walking am I. Maybe I’ve been walking backwards in landscape in my language, the Cherokee offer a different worldview. After an hour and half, I step out of my meditative trance and into another century. The footpath is swallowed in the intersection with a former logging road, deeply and recently rutted with tire tracks of a heavy-duty four-wheel drive pickup, maybe bear hunters out scouting next year’s hunt. The ghosts are gone. They passed this way, but their footpath has disappeared. Likely they would have kept going over Big Stamp, headed down to the Nantahala River and the town of Tomatly maybe 10 miles below. My dogs splash happily ahead through the muck but wait for me ahead at an old campfire where hikers stopped on the 20 miles Rim Trail that circles the ridges above Fire’s Creek. I eat my turkey sandwich I packed this morning, saving the last bites for both Merlin and Ben, who’s wallowing in more mud and shit. They will need baths later when we get home. The rain that has held off starts a faint sprinkle. It’s time to go. Back home, I’ll download the GPS data from my watch via Bluetooth to my iPhone. The satellite imagery will show my red line like ant trail ending up through the green ridge, the imaginary colors of the map in a winter world showing a palate of grays and browns in reality. 4 hours , 2200 feet, the data shows. But now the trail travels into my muscle memory. I have taken the experience into my brain and bones. I can feel the earth beneath my feet, leaning into the rise, my hiking pole balancing me coming down through the trees, the mountains rolling away to the horizon all around, breathing in the place I feel most at home, outside of time and technology. Nogwo usdi nunohi gega. Now the small trail walking am I.  James Salter made up his own rules on writing. James Salter made up his own rules on writing. I'm pleased to be included among some fine writers in the latest issue of the Great Smoky Review. Check it out at www.thegreatsmokiesreview.org. Check it out If I am to be truthful, fiction did not seem all that friendly when I was first confronted with a story and the expectation that I should write one. Second grade at South Park Elementary. Mrs Brown’s class. We’ve just read a paragraph about circus clowns. We have been assigned homework for what may have been the first time in our young lives, but certainly not the last. Write a story, my teacher ordered. I was paralyzed, close to tears. The story we had just heard pretty well-covered everything a seven-year old would know about clowns. What would I say? I could feel Mrs. Brown’s disapproval already. I was a failure as a second-grader. Then my mother had a revolutionary idea. “Why don’t you write about something else?” I don’t remember exactly what I wrote. I just remember that great sigh of relief. The freedom to write what I wanted. That was the important part, the starting point. So early on, I learned the first rule of creative writing. “You don’t have to write about the clowns you don’t know.” Later teachers would refine that for me into the workshop saw: “Write what you know.” A useful enough rule for an apprentice writer. Later on, I was given permission to write about what I didn’t know, which pretty much summed up my long career as a journalist. Contrary to what many may think, journalists aren’t know-it-alls, and certainly not experts. Journalists simply learn how to ask people who do know about certain topics, and translate those ideas into everyday English. Fiction works in a slightly different vein. As the composer Verdi once said. “To copy truth may be a good thing but to invent truth is much better.” Writing is such a subjective, strange endeavor. At its essence, writing is a mysterious mind meld between the writer and the reader. They are able to share a single thought in a single sentence through that marvelous code of alphabet, grammar, syntax, metaphor, all of which communicates thought, makes meaning through the largesse of language whether printed or pixilated. And we spend years in workshops and seminars, reading, writing, critiquing, experimenting, trying to figure out the rules of fiction or nonfiction. And there are plenty of worthwhile suggestions, rules of thumb for consistent point of view, pacing, voice, dialogue, all those elements of craft that provide the scaffolding for the art itself. If we just know the rules, maybe it would all be easier. So we ask mentors, we read guidebooks. I like Somerset Maugham’s dictum: “There are three rules to writing a novel….” (I’ve started with this and had students take up their pencils ready to scribble out the received wisdom.) “…Unfortunately,” Maugham continues, “no one knows that they are.” What I have discovered is that novelists have to create the rules of the game with each book they write. You break those rules once you’ve set them out at your own peril. The reader will know when you’re cheating. But rather than focus on the rules, I think writers are more in need of permission to play, to explore, to daydream, to pretend. It’s the grand game of What If. We need to write into what we don’t know from the starting point of what we think we know. If that be clowns, then put on your red ball nose and your big shoes and write. If you want to do zombies or Elizabethan ladies, Mexican migrant workers or Martians, go ahead and give yourself the permission to write the stories you want to read. So rather than rules, let me offer some suggestions from a writer I deeply admire. James Salter has penned some of the most elegant prose I’ve ever read, starting with his 1968 breakout novel A Sport and a Pastime, and 1976’s Light Years, about the disintegration of a marriage of a Hudson Valley couple. A former fighter pilot in Korea, a filmmaker in Hollywood, a world traveler, Salter writes the kind of sentences that writers would kill for. I keep going back to his novels, his memoir Burning the Day, and his exquisite stories, in which he seemed to break all the rules of what I had thought fiction could do. Salter died last year just after his 90th birthday, but I still revere him as an immortal when it comes to the words themselves on the page. These are his rules, which he pinned over his desk for reference while he wrote. Do not be eager to please. 1. TACT 2. Don’t feel obligated to write sentences. 3. No life is interesting that isn’t serious. 4. Write for readers like yourself. 5. Like Turgenev – that simplicity of telling that one trusts & loves. 6. Describe … Digress … Make leads (Forster!!!) … Open chapters beautifully. 7. Don’t write something they will recognize & accept. Write something that will astonish, that is completely different from their ideas & world & will alter them. 8. NO FINE WRITING. 9. Do not insist. Do not over-adorn. 10. Brief, lucid, mercilessly clear. 11. Don’t endorse narrowness, lack of intelligence. Instead concentrate on what they do know, their grace, valor, the glint of true light. 12. No “intellectual” conversations/digressions either from you or them. MAKE IT UNBEARABLE “Once in a while, forget logic, sequence, perspective, even chronology.” Salter was a high craftsman with an appreciation for what a well-written book can mean in a human life. To write a great sentence is, I believe, a worthy addition to the world and a worthwhile pursuit in this life we are given for such a short time. As Salter once wrote to a friend, “We must consume whole worlds to write a single sentence and yet we never use up a part of what’s available. I love the infinities, the endlessness involved…” So the only rule I would leave you with is this: write not so much what you know, but what you love. Dale Neal is the author of two novels, Cow Across America and The Half-Life of Home, numerous short stories and years of award-winning journalism. Neal holds an MFA in creative writing from Warren Wilson College. He teaches in the Great Smokies Writing Program and at Lenoir-Rhyne University’s Asheville Center for Graduate Studies. He lives in Asheville.  When Gil Jackson said he knew of a place off trail and way back in the Smokies, a sacred site to his people, I had to go see for myself. Gil grew up on the Qualla Boundary and lives now in Snowbird community. An educator and avid outdoorsman, he’s also a fluent speaker of Tsalagi or Cherokee, the intricate tongue only spoken now by about 200 remaining members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Gil has partnered with Barbara Duncan to teach Cherokee Level II at UNC Asheville. I’ve been sitting in on the evening classes, eager to learn the language that is native to the Blue Ridge before English was ever heard in these hills. Gil had mentioned making a field trip to Medicine Lake. I’d read my James Mooney, the great anthropologist who had chronicled the Cherokee’s myths, history and sacred formulas. Mooney recorded several stories of encounters between men and bears and a mythic body of waters where bears healed themselves. Families had handed down the tale of a old medicine man named Jaki-oo-sti, who earned his white hairs and wisdom with a chance encounter with a bear. Out hunting, he had shot the bear with his muzzleloader, but then the bruin started talking to him, pleading for him not to shoot again. “Something is wrong. We are not supposed to meet,” the bear told the man. “There is a fine line that divides our worlds and you have crossed over to mine.” The wounded bear asked the man to accompany him to a magical lake for healing. At the lake, the bear immerses himself in the waters and then resurfaces with his wounds completely healed. The bear shares a secret wisdom as to good plants, the wind, nature and animals. With the bear as his spiritual guide, the man sits in a cave with the Thunders, the beings who create the loud clashes in the sky during a storm. They use a long living snake as their bench. One by one, from youngest to oldest, the Thunders go out and make their noise, shaking the world. Just another of those Just-So stories, many people might think, but walking through the Blue Ridge with the thunder int he distance, or the little sounds that the little People may be playing tricks on you, or if ever see the shambling shape of a great bear in the woods, you realize the Cherokee were talking about their realities, not just imagining stories for a good campfire. There are places in our woods where you can feel the thin spaces and believe that there are creatures watching from the other side. Gil had heard of the place for decades. Oldtimers would say, “oh it’s just over the ridge there,” but no one seemed to know for certain. Then a healer from Oklahoma took him to a place in the Smokies, just above the Big Cove community on the Qualla Boundary. Gil later pinpointed the site on a topo map, as a place where three creeks flowed together at right angles from the north, east and south and headed west. X marked the magical spot. “That has to be it,” Gil said. Trouble was it had taken him 12 hours of bushwacking down a overgrown manway to the pond and then up the mountain again back to his car. But we were up for an adventure, all students wanting to learn more about the culture along with the worlds of Cherokee we were tasting on our tongues in our weekly classes. Out of the classrooms and not the woods seemed like a good idea. Six of us got a late start on Good Friday, with a slight sprinkle though the trees, but the weather was promising for the weekend. It was around 8 p.m. and getting dark before we made the top of Hyatt Ridge. Rather than push on another mile in the dark to site 44, we decided to pitch camp on the flats. Snapping poles for tents, readying for the night, firing up some water for dehydrated chili, chicken and rice, apples and cheese. We were settling in for the evening. Jordan brought out her well-worn paperback of scary stories to be told around campfires. Devon wanted to hear the one about the preacher in the haunted house. Will read the one about the Hook, and the escaped killer who leaves his signature hook in the side of a necking couple’s car. “The stories themselves aren’t so scary, said Jordan. “It’s what I think about them afterwards.” Gil started talking about things he had seen. True tales are the scariest once you think about them Like the old-timer he had brought to see the Medicine Lake. They had camped nearby, and they are sound asleep. Gil’s friend woke up, hearing the sound of footsteps in the woods. He could see a light floating toward the tent. Maybe it was the moon, but it came from the north and then retreated. Gil shook his head. Scary things happen on the reservation. Gil once hired some buddies to paint a rental house over in Big Cove. But they hastily left the house and wouldn’t go back. One man said he had sensed a presence, someone watching him. When he looked out the window, he saw the red bandana around the head of an old woman, but her feet wasn’t touching the ground. She was floating over the creek, glaring balefully at the paint crew. "A levitating lady is mighty scary," I joked, but no one was really laughing. We sat in the night, listening for what may be out in the woods. “Deyvon, do you know why the old people wanted to sit with a body overnight?” Gil asked. To keep witches away. When Gil’s father had passed, the family had sat vigil with the body in their small Baptist Church. His sister and brother-in-law feel asleep. But then the sister woke up and there was a wind that blew the door open. A man stood there. He came in and looked over the body of the dead man, but didn’t touch it, perhaps because it had been embalmed. He may have been a witchdoctor in search of a fresh liver to steal and eat. An owl hooted nearby, and we shuffled nervously on the logs we sat on, our headlamps peering out into the darkness of the Smokies, the endless nights over the mountains, the thin spaces between reality and imagination where things walk that haunt your dreams. Will and Deyvon shared the story of Spearfinger, one of the Cherokee’s most terrifying monsters. Spearfinger, once upon a time, could appear in any shape she wished, but underneath her guise was a stone monster whom no one could harm. She was most dangerous in the autumn, for then she could walk out of the mountains hidden in smoke from bonfires. One day, late in October, out of that smoke she appeared to a group of children, disguised as an old woman. She smiled at a little girl. "Sit on my lap, and I will brush your hair," she said. The innocent girl sat upon her lap and then, with her special stone finger, Spearfinger stabbed the child's side. The girl never felt a thing. Later the girl walked home, and that night she grew very sick. Then the villagers knew. Spearfinger had struck again. Fearing for their children, the people had a great council, and the medicine men came up with a scheme to dig a great pit. Then they made a huge bonfire, and when Spearfinger saw the smoke, she came down into the village and chased the young men right to the trap. Just as the medicine men had planned, she did not see the pit, and so she fell in. The monster was coming out of the pit, threatening to eat all their livers. Then a chickadee alighted on the witch’s hand. So the warriors shot their arrows at that hand, and true enough, that was where Spearfinger's heart was located. Spearfinger sank to the ground, slain at last. And the Cherokee still honor the chickadee, calling it ‘tsikilili or "truth teller." When we went to bed, Jordyn slept in her hammock with her boots on, both to stay warm and ready to run if Spearfinger, or a bear or a ghost came into the campsite. Gil kept seeing a bright light out of his tent and wondered why Jordyn was shining her headlight at him. But then he decided it was the moon. From my tent, I heard only the snores of my fellows, and the owls hooting close by. Barn owls are called ugugu in Cherokee, but sometimes sgili, when someone suspects the calling predator is not just a feathered bird, but a shapeshifting spirit. It is the same word for witch or ghost. The sun rose the next morning, reddening the eastern rim. We eat breakfast and set out for a day’s journey to find Medicine Lake. Coming down the trail to site 44, I see the bear bag cables strung by the trees, and the flash of a white tail ahead. “Awi tsigowatiha” "I see a deer." A good sign, an omen. Gil said that he always knew he was close to Medicine Lake when he reached one of the forks of Raven Creek. Each time, he would see a rainbow trout leap up out of the water as if in greeting. But the spirits of the place could be finicky. He had been up the same creek with a friend, Lamar Marshall of Wild South, who held a GPS in his hand. Gil warned against taking photos or mapping coordinates, which could disrespect or disrupt the power of the place. Lamar had his GPS device swept out of his hand by the current. They scouted up and down the creek, but never found it. We leave the Hyatt Ridge Trail and head west up over the ridge, finding a faint path marked with pink and blue ribbons. Later on the maps, I discover the name is Breakneck Ridge, perhaps an omen in itself. Wildflowers are in profusion with long views to the south. Along the way, single file on the elusive trail, we chatted and learned about each other. Jordyn had her camera, snapping photos along the way. A media communications major, she had her eye on a job as a journalist. Deyvon had finished his political science senior paper on tribal sovereignty and medical marijuana. Native Americans have built casinos in states that had previously outlawed gambling. Would tribes lead the nation in marijuana production? Gil was a font of knowledge, stopping to point with his hiking pole at the profusion of wild geranium, triangular blooms of trillium both pink and white, delicate Dutchman’s breeches, yellow lilies hanging their heads, bloodroot and toothwort. He showed us socchan, the spring green savored by the Cherokee who boil and sauté the leaves. Wadsi, too, better known as ramps, the pungent onion-like herb that sprouts in spring across the Smokies. The ribbons led up and out the ridge as we mad our way over windfalls, and blowdowns, toppled trees that blocked the trail. We stopped at the top at a hog wallow - a muddy puddle where wild boars rolled around and then rubbed their bristly bellies against mud caked tree roots. “That must be Medicine Lake,” we joked. Suddenly, the ribbons gave out. We scouted out the edge of Breakneck Ridge, but there was no sign of the distinct trail that Gil had followed at least twice before. Could it be hidden by a blowdown? Or perhaps the Little People were playing tricks on us. The sun drifted behind a gathering cloud cover. The space was feeling thinner. No need to go bushwacking downhill. Rather than plunge ahead and get seriously lost, surrendering our current condition of seriously confused, we retraced our steps over the next couple of hours We circled back to campsite 44 and ate our lunch. What had promised to be a warm day had taken on a slight chill as clouds covered the Smokies. We slipped on warmer shirts as our sweating bodies cooled off. Eating rolled-up tortillas with honey and peanut butter, we reached a consensus. We could go on down the trail and cut up the creek until we came to the Big Pond, but getting back out before dark was unlikely. Breakneck Ridge had been no picnic, no easy stroll. We were feeling the burn of hours of hard hiking. So we made our way back to our base camp, packed up our tents and gear, and hiked down to the cars parked at the bridge at Straight Fork, then drove on home. Gil apologized for not finding Medicine Lake, but there was no need for forgiveness. We had gotten what we had come for. We returned with our livers safe from any monster or witch and with our hearts gladdened. Maybe the Little People had misled us, but we had found our own healing waters, soaking in the spirit of these woods, in the footsteps of the first people who had hiked these hills for centuries before us, and in the company of friends that day. That was medicine enough.  When the world is too much with us, when the new fake news and our President-elect's stream of tweets are boiling the blood of too many of my friends fixated on Facebook and the future, I beat a hasty retreat to books to try to make sense of my fragmented and frightful days. I've fished out an e-book I downloaded into my Kindle a few years back, "Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation." Think of it as a kind of ethical or philosophical how-to guide when your world ends and you're stuck in the wasteland of the future glaring upon the smoking ruins of all your cherished assumptions of how things are supposed to work. Lear is a philosopher looking at the human possibilities of survival. His case in point is the story of Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow tribe in Montana, who saw the demise of a traditional way of life and the passing of the buffalo he had hunted as a young man. Plenty Coups refused to speak of his life after the buffalo, so that his story seems to have been broken off, leaving many years unaccounted for. "I have not told you half of what happened when I was young," he said, when urged to go on. "I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. Besides," he added sorrowfully, "you know that part of my life as well as I do. You saw what happened to us when the buffalo went away." Lear is trying to make sense of that strange insistence that Plenty Coups makes: "After this nothing happened." Actually plenty happened in Plenty Coups' life, taking up agriculture rather than hunting, lobbying Congress against transfers of Crow lands, even representing Native Americans at the 1921 ceremony inaugurating the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, DC. But that was a different life for this man, who had to surrender all hope that his old way of living could be resurrected. He had to find a new understanding - a radical hope - in living past his own history. Lear sees a lesson for us all in how Plenty Coups wrestled with his old/new life. It's the vulnerability all humans share in an always uncertain future that erodes the comfortable assumptions we have shared. In other words, how do you thrive in and not just survive the end of your world. "We live at a time of a heightened sense that civilizations are themselves vulnerable. Events around the world - terrorist attacks, violent social upheavals, and even natural catastrophes - have left us with an uncanny sense of menace. We seem to be aware of a shared vulnerability that we cannot quite name. I suspect that this feeling has provoked the widespread intolerance that we see around us today-from all points on the political spectrum. It as though, without our insistence that our outlook is correct, the outlook itself might collapse. Perhaps if we could give a name to our shared sense of vulnerability, we could find better ways to live with it." - Jonathan Lear. It may be only a day at a time that we feel our way forward, vulnerable, yes, but perhaps not so afraid, even radicalized by the notion that hope is still available in this America of ours.  This essay first appeared in June 2016, and I've received more response from readers than any other story I've done in my years as a journalist, In light (or the darkness) of our recent election, Asheville's anxiety and Thomas Wolfe's wisdom may be a useful tonic for our times. In 1983, I arrived in Asheville to take my first job with a daily newspaper. I was a cub reporter, covering night cops. I moved into Montford, on the curve of Pearson Drive in a three-story Queen Anne that had been divided up into apartments. The house like the neighborhood like the city had fallen on hard times. As our River Arts District has been called “sketchy,” the adjective “seedy” might have applied to all of Asheville back in the day. Asheville was like a fine lady who had seen better days, her Art Deco facades abandoned, the storefronts displaying nothing but dust. Downtown was deserted after dark. Gay men in those days when AIDS was just whispered about circled the Grove Arcade building in their cars, flashing their headlights, arranging trysts. The hookers walked Lexington, sad, stringy-haired women trying to support drug habits. Downtown was deserted after dark. I walked to the magistrate’s court, then in the ground floor of the County Courthouse, to check the warrants, looking for murders and domestic abuse, drunks and thieves and drug dealers. Those wayward citizens were housed upstairs in the courthouse, the best views in town through barred windows. The accused stared across the asphalt of Pack Square to the Downtown Club in the BB&T building where bankers ate in the afternoons. Way out Tunnel Road, the Dreamland Drive-In was still showing features at night, doubling as a flea market by day. Meanwhile The Mountaineer Inn flashed its neon Hillbilly down the hill from the Mall where all the department stores had fled over the still fresh Beaucatcher Cut. The French Broad River ran brown, frothy, forgotten down by the railroad tracks, tobacco warehouses and hobo camps. Summer nights, you could still hear the train whistles and the revving engines of stock cars down at the Asheville Speedway All beer was imported in those days, Budweiser was king and Schlitz, second. Coors had just fired its first Silver Bullets across the Mississippi. When the bars closed, we drove down to Biltmore, for early morning breakfasts at the Hot Shot Cafe, cats-head biscuits and saw-mill gravy. Down Biltmore, the Fine Arts Theater was showing "3 on a Mattress" and other porn. The Plaza on Pack Place was in its last days of frayed red carpet and rancid buttered popcorn. Long before the Zombie Walk, Asheville was sucking wind, the lifeblood seemingly drained away. I’ve interviewed hundreds of people over the years, asked how they arrived in Asheville. To a man and a woman, they say something like “I was called here. I felt an energy. This was home.” Back in the heyday of the New Age, (which some could argue, never has ended in our Cesspool of Sin), there were emanations from a giant crystal buried in the top of Mt. Pisgah. Now some say there is a vortex, a whirlpool of psychic energies, centered over Swannanoa or perhaps dancing over the stone obelisk of our favorite Confederate, savior and slaveholder - Gov. Zebulon Vance. Asheville emanates a vibe, a feel, an intuition, a hunch, a hankering. The drum circle in Pritchard Park with the newly retired Boomers banging out their different beats. I suspect our city has the feel of a summer camp. We are all campers, swimming in mountain cold currents, weaving baskets to carry our own meaning, making lanyards for our whistles through the cemetery. We recapture something of our childhoods. Something lost and by the wind grieved, the ghosts of ourselves. Who said, "You Can't Go Home Again?" You can’t talk of Asheville without talking of Thomas Wolfe. After a childhood of Tarzan and comic books, Wolfe was the first writer I had read who dared to write about real life. I was 16, the perfect age to hear Wolfe's weird goat cry. In “Look Homeward, Angel,” Wolfe put me by the bedside of Ben when he died in the upstairs. I walked with Eugene on Pack Square, when he saw his father’s stone angels come to life, when he saw his brother’s ghost in this town. And I reread Wolfe again, when I moved to his hometown. Tom was dead right what pebbledash stucco feels like when you rub your hand against the wall on the porch of a Queen Anne. What the wind feels like whipping up Walnut Street. I walked to Riverside Cemetery to pay my respects to the writer who pointed me home. I kissed the top of the granite headstone where 6-foot-6 Tom sleeps in the warm mountain dirt. Asheville is small town. Asheville is large. She contains multitudes. Natives and newcomers, the Patton Avenue cruisers and the commune crowd, hippies give way to hipsters give way to the Travelers, those unbathed backpackers with their mongrels on ropes taking up residence on sidewalks. "Keep Asheville Weird." "We Still Pray." "We Still Lay." "Support Local Food." "Don’t Postpone Joy." We wear our city on our car bumpers locked in the rush hour crawl over the Bowen Bridge each evening, headed straight into the sun. We have coaxed the tourists to come again, 9 million a year. We are Beer City. But we’re still a BYOJ kind of place. Bring your own job, or join the overeducated wait staff trying to make ends meet. Who can afford home here now amid all the hotels for the upper-upscale? We are worried - has Asheville jumped that shark in the French Broad River? Not just Asheville, America, still reeling from the reality show ending of our recent election. Rising inequality. Social media. Social anxiety. Ferguson, Staten Island, Baltimore burning, Baton Rouge, Dallas, Oklahoma City, Minneapolis, Charlotte. Nasty women. Deplorables. Black lives matter. Blue Lives Matter. All lives matter. Can we agree that anything matters any more? I keep turning back to Wolfe, to what would his last word, the ending to the novel, “You Can’t Go Home Again.” “I believe we are lost here in America, but I believe we shall found…. I think the life which we have fashioned in America, and which has fashioned us, the forms we made, the cells that grew, the honeycomb that was created, was self-destructive in its nature and must be destroyed. I think the true discovery of America is before us. I think the fulfillment of our spirit, of our people, of our mighty and immortal land, is yet to come. I think the true discovery of our own democracy is still before us. And I think that all these things are certain as the morning, as inevitable as noon.” Wolfe warns us of an enemy, with us from the beginning, and still with us in Asheville and in America– “single selfishness and compulsive greed.” It’s not just my Asheville. It’s our Asheville, our Appalachia, our America. We share a city, a country. We share an endless yet ever-ending story. The book that Wolfe wrote, that we write is not closed yet. We turn the page.  "Gayotli Tsalagi Tsiwoniha." ("I speak a little Cherokee.") It's intimidating introducing yourself to a roomful of strangers with words that seem to bunch up in your mouth, rather than trip off your tongue, but everyone was game. "Osda," or "Good," the students encouraged each other. The group included a firefighter from Florida, an academic from Boston, a retired Navy veteran, enrolled members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and me, a curious journalist, intent on learning more about Western North Carolina's first language. For the past few months, we've been taking online classes in Your Grandmother's Cherokee, a revolutionary method of learning the ancient language. Barbara Duncan, education director at the Museum of the Cherokee Indians, invited students last weekend to her home in Whittier, a farmhouse with expansive views of rolling pasture and blue sky, the perfect setting to practice a little Cherokee. It's one thing to see the words created on a computer screen. It's another to hear the words roll off the tongues of living fluent speakers, like Gilliam "Gil" Jackson. Jackson grew up and still lives in Graham County's Snowbird community - among the Eastern Band's most traditional strongholds. For the past decade, he's taught a language camp for the youngsters in Snowbird. His students are so good, he can drill students to add and subtract using Cherokee. Next year, he'd like to teach algebra and geometry in Tsalagi. But Jackson admits it's an uphill battle. There are only about 100 to 200 fluent speakers among the tribe's 15,000 members, mostly elderly. He knows only of about 50 youngsters who are serious about learning the language. Jackson calls it being hungry. Why learn to speak a language that has been seriously in decline in the past few generations? That's like asking what is the use of the trillium wildflowers that grow on mountainsides, well away from trails where humans might stop and admire them. Trillium, by the way, has an interesting name in Cherokee or Tsalagi that means thunder and lightning. And no, I have no Cherokee blood that I'm aware off. I hail from hearty Scotch-Irish and German stock, a long line of dirt farmers who settled in the Carolinas and the Appalachians. But I am curious about how language and landscape are intertwined. People talk differently in our parts. And not so long ago, the King's English was an alien sound in the mountains. To talk the talk of the Tsalagi is to walk a ways in the moccasins of a proud people, to catch a glimpse of the way they saw the world around them. The Cherokee left their names on the land they inhabited for centuries before the arrival of Europeans - from Swannanoa to Cullowhee, Cataloochee to Tusquittee, which means "where the waterdogs laughed." Asheville was once called Tokiasdi, or the "place where they raced," perhaps referring to canoe races at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers. Cherokee is among the world's 7,000 languages, but linguists estimate half may be extinct by the end of our 21st century. A language may be dying off every 14 days around the world, UNESCO has reported. But the people I sat with Saturday want to make sure their language doesn't die. Even though Sequoyah devised a syllabary to document the language, a first among Native American tribes, that still doesn't make Cherokee a living language if no one is using it on a daily basis to joke with their kids, talk to their relatives, or dream at night. Your Grandmother's Cherokee is the brainchild of John "Bullet" Standingdeer, who grew up on the Qualla Boundary. As an adult, Standingdeer was secretly ashamed he couldn't memorize and master Cherokee. For adult learners who know only English, Cherokee's long compound words can sound meaningless. Ask a fluent speaker for help and they can only repeat the words they learned as children. They can't say how the words change tense or meaning. But Standingdeer kept searching for the logical patterns, and discovered while the words changed, certain sounds or syllables remained constant, offering a clue to underlying structure. For Standingdeer, it was like locating the Rosetta Stone. Cherokee actually conjugated its long verbs consistently and logically enough for a computer algorithm to predict the forms. Standingdeer applied for and won the patent for that algorithm that is the linchpin to the Your Grandmother's Cherokee website. Cherokee's polysyllabic words work as complete sentences rather than individual nouns and separate verbs. And Cherokee is much more precise and tactilely nuanced than English and European languages. There are different forms of the word to give for example, if you are handing over a cup of liquid, a bowl, a pencil, or a piece of paper. It's also interesting to discover what words the Cherokee didn't traditionally use, like "respect." Jackson said respect was something the Cherokee would assume in a person's behavior, not just to pay lip service. Likewise, there is no word for "please" as in "please, help me." The Cherokee assume if you ask for help, you will be given it. No need to beg. And Cherokee has always been a flexible language, inventing new words with old concepts. When Cherokee first encountered an African elephant, they called it "kamama utanu," or "great buttterfly," since the pachyderm's great ears resembled wings. They are also inventing new words for technology to fit their tradition. "Devil's box" may be the best term I've ever heard for the ubiquitous computer Jackson applauded the Your Grandmother's Cherokee system. "If you can teach a methodology, then second language speakers will just fly," he said. Eva Garroutte grew up in Oklahoma as an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation. She has spent years listening to fluent speakers, but she couldn't get the hang of it until she encountered Standingdeer and Duncan's system. Her Cherokee name is "Dawa" or "flying squirrel" - the animal that can negotiate between the world of mammals and the sky of birds. Your Grandmother's Cherokee works like that bridge between fluent speakers and adult learners, said Garroutte, now a Boston College sociologist. "You can figure out something that your ancestors thought centuries ago because they left traces in the language," she said. "It's such an elegant language that does all these cool things. You can spend your life learning it," Garroutte said, who can carry on conversations. There are other clues as how the Cherokee viewed people as well as the landscape. Anger is a passive construction, something that happens to you like getting sick. Among the emotions as expressed in Cherokee, happiness doesn't just happen. It's an active verb along with being thankful. The familiar world of Western North Carolina looks a little different to me these days with new words to roll off my tongue, and how the lilt of Cherokee mimics the mountains, the rise and fall of ridges and coves. My favorite word, so far, in Cherokee?Agwasgwanigoska. "I am being amazed." |

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed