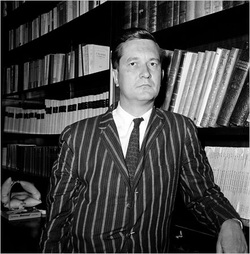

Styron as young literary lion You can’t count me as any kind of Pollyanna. Give me a few overcast days in midwinter, a riff of Miles’s horn on the radio, and I’ll turn blue with the best of them. But melancholy can be a pose, a romantic notion that the tragic is always more interesting than the comic, the mistake too many younger and serious writers tend to make. I’ve been mulling over melancholia lately while reading William Styron. With the recent arrival of Styron’s Selected Letters, I’ve been re-reading his 1951 debut “Lie Down in Darkness” – a bestseller that propelled the 25-year-old writer into instant celebrity. Soon he was padding around the literary lion’s den with the likes of Mailer and James Jones and other red-blooded he-men writers of the Great American Novel. Styron eschewed what he called the “Hemingway mumble school,” tending more toward the purplish expanses of his fellow Southerner Thomas Wolfe. “When I mature and broaden, I expect to use language on as exalted and elevated a level as I can,” the young Styron wrote his Duke mentor William Blackburn. "I believe that a writer should accommodate language to his own peculiar personality and mine wants to use great words, evocative words, when the situation demands them.” I hadn’t read Styron’s novel in 35 years, not since I breezed through as a junior in a contemporary American Lit survey in college. In my bifocaled hindsight now, Styron’s book reads like a young man’s overly romantic vision, not of the Good Life, but of the Marriage Gone Bad – the sorry saga of the alcoholic lawyer Milton Loftis, his estranged Southern belle of a wife, Helen, and their two daughters, the impetuous Peyton, and the special needs daughter, Maudie. The novel charts a single day in August, 1945, just weeks after the bomb feel on Hiroshima. Peyton has committed suicide in New York, and her body had been borne back by train to to the fictional Port Warwick in Tidewater Virginia. Over seven sections and 400 pages in my water-damaged Signet paperback, the book follows Loftis and Helen’s separate journeys to the cemetery, and through their back story of their sad marriage. The opening is masterful, putting “you” into the steamy Southern landscape as the train pulls into the fictional Port Warwick. Throughout, Stryon has a muscular omniscient point of view that can see a fly land on a fat man’s face or how female golfers have to tug at cinching panties, an authoritative voice we don’t hear too often in our more ironic times with the nebbish narratives that have followed after David Foster Wallace. Stryon labored mightily over the book, complaining in his letters how agonizingly slow he found writing. Unfortunately, it shows in the books, which becomes a long march through gloom, leavened by very little humor. There’s a reason that Shakespeare has a jester in King Lear, for a little comic relief and to add to the absurdity. Styron’s idea of comedy is sarcastic, picking on the wide-eyed Negro stereotypes of the time. In the Jim Crow era, pre-Civil Rights South before airconditioning and television, Styron unveils a benighted look at the prevailing racist attitudes. It’s not pretty to read. But it’s still a young man’s notion of tragedy that turns his book into melodrama, the scenes slow to the pace of sticky molasses. There’s pathetic fallacy aplenty as the landscape echoes the alcoholic mood swings of Loftis or the high strung neuroses of Helen, and too often, Styron’s swagger wades too deep into the purplish patches that tripped up Thomas Wolfe. In the end, I had to lay down “Lie Down in Darkness.” I don’t think too many readers will be taking that novel up, nor his “Confessions of Nat Turner” or even “Sophie’s Choice.” Styron himself admitted that his latter fame probably depended more on his slender memoir, “Darkness Visible” about his courageous battle against a debilitating chronic depression, than on his fatter, darker fictions. Styron reads now like a boy whistling in the dark, trying to keep his spirits up, but afraid to truly play. I’m not arguing for sweetness and light, but that a maturer vision sees how to balance the light and the dark in any artful composition. I hold to what one of my teachers, Allan Gurganus, always insisted on: that humor and horror must go hand in hand, hopefully, in a single sentence. Mac McIlvoy suggested in one of his topnotch workshops that writers have to learn to “play in the dark.”

2 Comments

|

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed