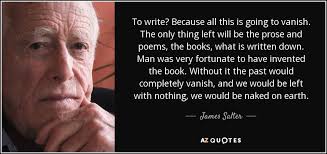

How do we know where we are online? It’s easy to make fun of the Twitter zombies, those lost people head down tapping away on their iPhone as they walk or drive. But truth be told, I’ve bumped into things. I’ve spent minutes transfixed by Steve Jobs’ legacy. The smartphone makes us all look dumbstruck. We are social media suckers, scrolling down, looking for friends for enemies, for our next like, our next outrage. What’s Trump saying now on the stump? Who’s feeling the Bern? Aw, what a cute puppy. We see our world delivered in bits and bytes and digestible data. We lose sight of our surroundings. We are lost to physical reality with the virtual world in our hand. I’ve been thinking about place and its importance of it in an increasingly data fragmented world. Google maps will gladly show us the street scene, but how do we understand where we are? Remember Nature? What do we think when we hike out to a gorgeous vista or up a great trail. Do we automatically take a selfie on top to post to Facebook? Are we conquering the mountain or are we its companions. I’ve been turning to Barry Lopez, one of our foremost writers and thinkers about place. How do we think about nature. Here’s Lopez on “A Literature of Place.” These seem like instructions for re-enchanting our world, breathing as animals on our planet, finding the human home in the cosmos. “How can you occupy a place and also have it occupy you? The key, I think, is to become vulnerable to a place. If you open yourself up, you can build intimacy. Out of such intimacy may come a sense of belonging, a sense of not being isolated in the universe. How does one actually enter a local geography? (Many of us daydream, I think, about re-entering childhood landscapes that might dispel a current anxiety. We often court such feelings for a few moments in a park or sometimes during an afternoon in the woods.) To respond explicitly and practicably, my first suggestion would be to be silent. Put aside the bird book, the analytic state of mind, any compulsion to identify and sit still. Concentrate instead on feeling a place, on deliberately using the sense of proprioception. Where in this volume of space are situated? The space behind you is as important as what you see before you. What lies beneath you is as relevant as what stands on far horizon. Actively use your ears to imagine the acoustical hemisphere you occupy. How does birdsong ramify here? Through what kind of air is it moving? Concentrate on smells in the belief you can smell water and stone. Use your hands to get the heft and texture of a place - the tensile strength in a willow branch, the moisture in a pinch of soil, the different nap of leaves. Open a vertical line to the place by joining the color and the form of the sky to what you see out across the ground. Look away from what you want to scrutinize in order to gain a sense of complexity, the sense that another landscape exists beyond the one you can subject to analysis. A succinct way to describe the frame of mind one should bring to a landscape is to day it rests on the distinction between imposing and proposing one’s views. With a sincere proposal you hope to achieve an intimate, reciprocal relationship that will feed you in some way. To impose your views from the start is to truncate such a possibility, to preclude understanding.”  James Salter died at age 90 in June, almost a year after I gave this lecture at Mt. Holyoke College at the annual Warren Wilson College MFA alumni conference. Since I first encountered his stories 30 years ago, Salter has been the writer who most mattered to me. The Arrogance of Failure: On Reading James Salter “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.” James Salter, All That Is In the summer of 1984, half way into Orwell’s fatal year, at the dawn of Reagan’s supposed Morning in America , the August issue of Esquire arrived in my mailbox. “Take This Magazine on Vacation! The Best of Summer Reading,” The self-referential cover featured two fair-skinned representatives of what were then called Yuppies, a young man and woman snuggling in a beach hammock over the latest issue of the venerable men’s magazine. Beaming at the camera, they had evidently already read the contents and were knowledgable of useful tips for the male of the species to pick out an Oriental rug, properly pack his fly fishing rod, mix a pina coloda or book the best B&B for his next assignation. But for me, Esquire had gone one further with its first fiction issue, offering not just the motto “Man at His Best,” but my first real tips on “How To Be a Writer.” The cover listed a lineup of heavy hitters whose names I knew and books I had already devoured; Updike, Doctorow, Ken Kesey, the eternally ubiquitous Joyce Carol Oates, all vetted by guest editor Irwin Shaw who had just died that spring. But there was one author I had never encountered. His thumbnail picture inside did not do him any favors: a mustachioed man in a floppy fishing hat and plaid shirt, like everybody’s unfashionable dad on vacation, a serious mismatch with the elegance of the sentences that followed. The story was titled “The Fields at Dusk." which began with the line “Mrs. Chandler stood alone near the window in a tailored suit, almost in front of the neon sigh that said in small, red letters PRIME MEAT.” Mrs. Chandler, Vera her name, is a middle-aged woman living beyond the breakup of her marriage, a hasty love affair with her handy man. The story is set in hunting season, geese flying south in broken formation, shots resounding in the distance. Vera is, of course, wounded in her own way, forever grieving the death of a young son drowned in the sound. The story ends with an image of one of the hunted geese, felled by buckshot, bleeding out in the wet fields. Cut to a woman alone in a beautiful house. “She went around and turned on lights. The rain was coming down, the sea was crashing, a comrade lay dead in the whirling darkness.” I want to say that the words moving from the page inside of me eclipsed that August afternoon. I looked up and must have blinked. Things looked different. I was different. The unexpected difference that an encounter with art makes in our perception. I dove back in, rereading the story. Who was this guy and how had he worked this spell over me? Tom Jenks’ succinct biographical note takes a brief measure of the man: “James Salter was born in 1925 and grew up in New York City. He served 10 years in the Air Force, but resigned in 1957 with the publication of his first novel A second novel vanished, Salter said. “Without a trace.” He was then 40, with four children and “did not know what would happen.” Seven years later, he published one of the great literary works of our day. The story of a young American’s affair with a French Girl, “A Sport and a Pastime is a tour de force of erotic realism and displays the sophistication and brilliance that are now his trademark. Throughout his career, Salter has been more appreciated by more serious literary authors than has any other modern American writer. His writing slips almost mysteriously in and out of various characters’ points of view, creating not a single effect, but by the end of each story a multiplicity of effects that carry the reader deep into the meaning of human experience.” Jenks was right about the other writers’ praise. Richard Ford, Mr. Rock Springs, the Sportswriter himself, would declare: "It is an article of faith among readers of fiction that James Salter writes American sentences better than anyone writing today." As Susan Sontag observed, “Salter is a writer who particularly rewards those for whom reading is an intense pleasure.” James Salter of course is an invention. He was born Horowitz, to a successful Jewish family living in Manhattan. He followed in his father’s footsteps, a cadet at West Point, but missed the second World War. He became a pilot in the then Army Air Corps. And once crashed into a suburban New Jersey house on a training mission, the only causality being his pride. He hankered after the fame he saw in Jack Kerouac, a year or tow ahead of him at the prestigious Manhattan prep school, Horace Mann. When choosing a pen name, he wanted to make a statement, cementing his place in English letters. He wanted to call himself at first "Psalter" with a "P" as in the Psalms, but fortunately was persuaded that may be over the top. Salter seems like Hemingway without being a jerk, a heroic writer who writes of beautiful lives, of jaunts through Paris and the French countryside, of elegant lives in the best haunts of Manhattan. His first novel turned into a movie starring Robert Mitchum. He would go onto to write screenplays himself, direct movies, pal around with the likes of Robert Redford. Any summary of Salter’s career makes him sound like the older brother of The World’s most Interesting Man, the tongue-in-cheek shill on the Dos Equis beer commercial, “Stay thirsty, my friends.” The kind of guy, you want to go drink with him or sleep with him, depending on your own predilections. That impossible resume, the irresistible lyricism spoke to me. In his Esquire note, Jenks didn’t quite come and say it, but I knew I had found my “writer’s writer” in Salter. A “writers writer” is a the left-handed complement, code for someone who can’t sell commercially, only a step away from the cult writer with his feverish fanboys, easily forgotten. But in joining the sect of Salter, I was making an unconscious bet that I could be a writer as well, even if I failed and fame eluded me as it had Salter for so long. In the intervening 30 years, I would attempt to read anything and everything this man would write. At Malaprop’s, I found the North Point paperback of “A Sport and Pastime, which Reynolds Price lauded as “nearly perfect as any American fiction I know.” Hard to go wrong with a loose episodic theme: couple fucks their way through France, It remains the most sensuous book I've ever read on sodomy. yet something else more mysterious is going on than scenes glimpsed through a vaseline-smeared soft porn lens. This torrid affair is filtered through the imagination of a first-person narrator who acts as more than just a voyeur, but like a detective of a hidden reality, a shimmering essence underneath flesh. We see a clue in this passage to Salter’s method as a writer, and his effect on the reader: “Some things, as I say, I saw, some discovered, and some dreamed, and I can no longer differentiate between them. But my dreams are as important as anything acquired by stealth. More important, because they are the intuitive in its purest state. Without them, facts are no more than a kind of debris, unstrung, like beads. The dreams are as true and manifest as the iron fences of France flashing black in the rain. More true, perhaps. They are the skeleton of all reality.” (ASAAP, p. 58) “A Sport and a Pastime” could be dismissed as a tour de force, a one-off, high class Henry Miller, but his 1975 novel, “Light Years” made me an acolyte at his bright altar of crystalline sentences. I found a first edition in the old Captain’s Bookshelf in downtown Asheville and devoured it, then reread it, then pushed it on all my friends. In 1985, I would write my very first annotation of this book in my application to Warren Wilson, seeking admission into the MFA, following after Salter into this priesthood of prose. Salter said the book was inspired by a line from Jean Renoir: “The only things that are important in life are those you remember. That was to be the key. It was to be a book of pure recall. Everything in the voice of the writer, in his way of telling. I had a list of sufficiently inspiring titles, Nyala, Mohenjodaro, Esturial Lives. I was writing to fit them, though in the end none survived.” The story is the close dissection of a marriage, a successful, higher income family living on the Hudson River, making forays into the city. Their daughters grow up, their friends come and go, their love for each other slowly dissipates. Here, Salter had reinvented himself once more, no longer the military man. In interviews, he said the invention was largely conscious. He had come from such an exclusively male domain, a masculine life, he cultivated in his writing or attempted, a more feminine side. “Writing is filled with uncertainty and much of what one does turns out bad, but this time, very early there was a startling glimpse, like that of a body beneath the water, pale, terrifying, the glimpse that says: it is there.” Again that elusive narrator hovering in the background, the first-person observer, the creator, mysterious as Jehovah, that still sure voice, a man invited to their dinner parties, a dining companion, a neighbor, a voyeur, but always a witness to the brilliant wreckage of the years. There are passages that linger, like Viri shopping for hand-tailored shirts, the lilt of bright dinner conversations, the clink of champagne flutes, the good life to be envied, but the restlessness of love slowly draining away from these relationships. The world is made of bright things, shimmering, but somehow infinitely sad in how it slips away from our warm hand. "Life is weather. Life is meals. Lunches on a blue checked cloth on which salt has spilled. The smell of tobacco. Brie, yellow apples, wood-handled knives.” Salter can sometimes read like a sensual litany. There is a romance around the aura of detail he summons. Like well-placed ad for Pottery Barn. But then Salter can sound a note not readily seen in contemporary literature, or at least not since wisdom. Something out of Emerson or Ecclesiastes. But that easy elegance can be mistaken for a shiny superficiality, and Salter was stung by nasty reviews. The Times Book Review called it "an overwritten, chi-chi, and rather silly novel." Anatoyle Broyard deplored the character's arch names. Viri and Nedra. Salter made the cardinal mistake of answering his critic with a letter. "Come on, Anatoyle.” The book, which Salter had seen as his bid for a breakout, did not do well, only 8,000 copies or so, even in those halcyon days when novels were still at the culture’s center. E.L. Doctorow would find commercial success, with 200,000 copies sold of his breakout “Ragtime.” And do not think that Salter, a man among men who once painted their kills on the sides of their fighter jets, does not keep score. Salter is that rare writer who takes on ambition and glory, and of course the bitter taste of ashes int he mouth, the toxins of failure, envy, disappointment. If the American outlook can be summed up in Howell’s observation: Americans love tragedies with a happy ending,” then Salter seems foreign, almost French in his sensibility. Rigorously unsentimental like Colette or Celine, Salter casts a hard clear look on life, rearranging the players into his art. Salter has always insisted that his method is not to invent, but to take from reality. He works from extensive notebooks of what he has seen and heard, in a sense preying even on his closest friends for his art. I was troubled by the New Yorker profile that appeared last year. How much of the detail for Nedra and Viri was lifted from a real-life couple, the Rosenthals, that Salter had known and attended their dinner parties in his Hudson Valley days. “The Rosenthals were amazed, appalled, flattered and offended. Salter had said nothing to them about his work. Had he been writing it all down, discreetly taking notes?” Yes, he’s made a habit of that. “It makes people nervous sometimes,: said his friend Peter Matthiessen. “You see him writing away under the table.” How much is stolen or lifted from reality, how much is invented and embellished, these issues concern me as both one of the last surviving American journalists and as a novelist? How much allegiance do I owe to the private lives of others? Does the artist become somewhat of a parasite, a vampire, sucking the shiniest bits of soul from the people around him to serve his art? But those are topics for another paper, for the conversations around the dinner table. (Keep an eye on me. I may be taking notes under the table.) The literary life of course is not solitary. Writers need other writers, as much as they need readers. Henry James talks with Turgenev, with Howells, with Edith Wharton. Hemingway drinks with Fitzgerald in Paris, talks with Gertrude Stein. Franzen and DFW. Just as this gathering of Wallies has been crucial to my own survival as a writer for half my life now. We rarely hear from readers, but other writers tell us who we are. In his memoir, “Burning the Days,” Salter pays his tribute to Irwin Shaw, the writer he befriended in Paris, the first real writer he had met. Salter writes that “the truth was in the beginning, he saw in me the arrogance of failure. I had written two books, but the power I had was that I had accomplished nothing. My strength, like the evil-tempered dwarf’s, was that my name was unknown. He, on the other hand, was a writer of magnitude.” Shaw would warn his protege, that Salter perhaps relied too heavily on his lyrical talents, while Shaw was a narrative plowhorse. "Burning the Days” is his memoir, an elliptical account of what he considers worth saying about his life and career. It's been a kind of scripture for me on how to write and survive the writer's life. I keep rereading over long conversations with the critic and editor Robert Phelps. They met when Phelps had sent him a note in admiration of “A Sport and a Pastime,” intelligent praise. They met and began a correspondence that has been collected in the 2010 book “Memorable Days.” Phelps would guide his reading, introducing him to Isaac Babel, to Henry Green while downplaying others. “Faulkner is a terrible writer. He may be a genius but he’s a disgraceful writer.” Phelps would say. According to this critic, the 19th century novel had died with Ulysses, the writer pretending he is invisible, above all his characters. “It was the voice of the writer, Phelps insisted, that was the first and definite thing. Joyce and Proust with their forays into stream of consciousness and memory, commentary on character’s motivations, instead of portrayal of action, had pushed the novel form into a cul-de-sac. A second form is the writer speaking through character, inhabiting them, Henry James or Fitzgerald in Gatsby, or John Berryman Henry in the Dream Songs. The third form of the novel is the confessional, the first person, the writer standing before you. Salter quotes Phelps: “The original form of storytelling is someone saying, I was there and this is what I beheld. We are coming back to that. The mainstream was story, like the Bible, like Homer.” Somehow, Salter seems to inhabit all three forms, shifting easily in a third-person omniscience above his characters, diving deep into their psyches, while standing off to the side as a physical witness. He is everywhere and nowhere. Despite a long life, Salter has not exactly been productive. He turned a screenplay for Robert Redford into a 1979 novel “Solo Faces” about the heroic lives and failures of mountain climbers in Europe’s Alps. His stories came out as “Dusk” in 1988 and won the Pen Faulkner award. He revised his early flying novels “The Hunters” (reissued by Jack Shoemaker at Counterpoint in 1997) and “Cassada,” which was published in 2000, a rewrite of his 1961 sophomore flop “Arm of Flesh.” Then there was the inevitable cookbook, “Life is Weather,” written with his second wife, Kay Salter, an elegant book of days drawing on reminisences and favorite recipes. Salter has waited his turn, as an apprentice in Paris and the Hudson, as a teacher himself at Iowa Worksop, the writer’s writer waiting for readers. And at age 87, publishing his long awaited novel, his summary of a career. “All That Is.” You can see Salter combining all of his world, both the military career and the bookish world, the pursuit of both war and women, in the character Philip Bowman, who drifts through New York’s publishing world for a lifetime, from the 1940s up into the 1980s. The criticisms have followed him, afraid to ever again be accused of writing a silly, superficial book, he toned down the lyricism, what Irwin Shaw had cautioned him against way back in their Paris days. In its loose episodic blow, the book actually builds to a shocking sexual betrayal that provides the emotional climax I am still ambivalent about. Bowman is betrayed by a lover with whom he had bought a vacation house in the Hamptons. In revenge, he seduces the woman’s daughter, whisks her away to Paris, has of course the rear entry lovemaking, and abruptly abandons her. I believe I put the book down, my jaw dropping. I corresponded with Robert Boswell, my last teacher during my Wally sojourn. He and Toni Nelson had just hosted Salter in a writer’s visit to the University of Houston. Me: “ I’m not at all sure what I think about Bowman's betrayal of that girl in Paris. A little too cold and cruel, French, maybe, for my Puritanical tastes, and I'm not sure the novel ends so much as fades off. But other than A Sport and a Pastime, I'm not sure that Salter has ever nailed an ending in a novel.” Boswell’s reply: Salter: Her mother had not only messed him over in matters of the heart, she'd taken his house. Of course, he wants to get even, but I wasn't thinking that way at all when I went with them to Paris. I was just as duped as the girl--one of the most thrilling episodes I've ever read.” But unlike his protagonist, Salter doesn’t just dump the character. In the penultimate chapter, we see the girl, Anet, later at her wedding day in 1984, then again in Salter’s strange mastery of time, a flashback to the dramatic confrontation of mother and daughter back from Paris, having slept with her mom’s former boyfriend. “He wanted to show you were a little slut. He didn’t have to try very hard. You know, he’s 30 years older than you. What did he do tell you he loved you?” The novel’s final chapter finds Bowman with yet another woman, frolicking in the sea. But later on land, tending his garden, he catches himself with the realization that under his tennis shorts, he has the legs of old man. “He was too old to marry. He didn’t want some late, sentimental compromise. He had known too much for that. He’d been married once, wholeheartedly, and been mistaken. He had fallen wildly in love with a woman in London, and it had somehow faded away. As if by fate one night in the most romantic encounter of his life he had met a woman and been betrayed. He had believed in love - all his life he had - but now it was likely to be too late.” The book trails off with Bowman looking ahead to a trip to Venice, maybe in November. Which leaves me ambivalent. Is that truly “All There Is”? Bowman, though he fought in the Pacific, is no hero. Nothing seems to deeply change in his personality, which may be Salter’s exact point. No heroics here, only survivors for a time. And in his last novel, likely his last, this faithful reader saw at last the pattern, a disturbing figure in the carpet. Following the writing of one writer obsessively gives a sense of the more unconscious, unsavory obsessions. Salter is no fan of the mere missionary position. Every woman we see from behind in most every sexual scene. The obsession with anal sex starts raising unsettling questions about Salter. Yes, he is a master of prose, but with that subtle confusion of narrator, character and author, Salter is seen by more than a few female critics as an antiquated throwback to the Rat Pack days of a man’s man’s world where all women are taken not in love but in lechery, and always from behind. (See the online debate between Roxana Robinson and Katie Roiphe “Is James Salter a Sexist.”) I am aware in writing this essay, in going through my collection of Salteralia and revisiting his influence, that I have fallen prey to hero worship. There’s always that masculine insecurity, the eternally adolescent need for role models: Am I doing this manhood stuff right? Let alone the anxieties of a writer: Will I ever find fame, perhaps a little fortune. Will I be loved and admired? This sounds blindingly obvious, but I’m not sure that Salter, or for that matter any other writer, or another human being, is a reliable guide for how to live your own life or write your own books. Salter sings of himself, of what he has seen in the world. He is a survivor. I can admire his sensibility, but I cannot steal it through imitation. Writer’s lives serve as warnings. And we can only envy the shiny surfaces of others. Heroes are by definition, fallen. The flutter of flags, the beating of the heart, in what is a lost cause, a hopeless battle, a last stand. The golden age of the novel is long gone, if there ever was such a mythic realm. We are living in the ruins of Dickens London, Proust’s Paris has crumbled like the madeline cookie, Yoknaptawapha has been paved over with Super Walmarts and Chick-fil-A’s. In “All That Is,” Bowman, who has made his career in publishing novels, reflects: “The power of the novel in the nation’s culture had weakened. It had happened gradually. It was something everyone recognized and ignored. All went on exactly as before, that was the beauty of it. The glory had faded, but fresh faces kept appearing, wanting to be a part of it, to be in publishing, which had retained a suggestion of elegance like a pair of beautiful, bone-shed shoes owned by a bankrupt man.” But Salter says this still matters, that amid the faded glory that the literary life is heroic. “When was I happiest, the happiest in my life? Difficult to say. Skipping the obvious, perhaps setting off on a journey, or returning form one. In my thirties, probably and at scattered other times, among the weightless days before a book was published and occasionally when writing it. It is only in books that one finds perfection, only in books that it cannot be spoiled. Art, in a sense, is life brought to a standstill, rescued from time. The secret of making it is simple: discard everything that is good enough.” So in keeping with Salter’s method, let me trail off here, rather than end with any grand conclusion. I’ve gathered my episodes, polished them, flung them at you, the audience, suggesting this is “All That is.” Perhaps what I should say is that James Salter has shown me not how to succeed as a writer, but how to fail and still persist. Following his example has taught me the long toil in this work we do, to encase the fine detail of the world as in amber, to bring out a brilliant shard that suggests a lost wholeness. The life spent trying to make meaning, make literature can be rich and rewarding, but also full of failure and frustration. We drink from a bittersweet cup, ashes always mixed with wine, and we are forever thirsty. In his memoir, in the chapter titled “Forgotten Kings,” Salter writes of his friend and mentor: “Somewhere the ancient clerks, amid stacks of faint interest to them, are sorting literary reputations. The work goes on eternally and without haste. There are names passed over and names revered, names of heroes and of those long thought to be, names of every sort and level of importance. Among them is Irwin Shaw’s” he writes. And I would add among those heroes the name of James Salter.

8 Comments

|

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed