The satellites are watching me make my way up a 45-degree incline, tracking a faint trace uphill from Fire’s Creek in the Nantahala Forest. It’s a cool, overcast day with the smell of rain in the air. I’ve driven all morning down from Asheville to Clay County, just north of the small town of Hayesville. There are plenty of trails closer to home, but I wanted to experience this short jaunt, to see for myself what this landscape’s first human inhabitants might have seen, to follow in the footsteps of ghosts and forgotten history. I’ve discovered this trail by happenstance, reading of the ancient Cherokee network of footpaths that crisscrossed the Southern Appalachians. Most of the major trading routes they followed have long since been paved over by modernity and asphalt. Where the tribe once walked, tourists and retirees zip along in SUVs and RVs. But a handful of the untouched, original trails remain, documented by the obsessive Cherokee pathfinder, Lamar Marshall of the Wild South preservation nonprofit. Marshall has made it his mission to travel these old ways. This morning, I’m traveling a 2.5-mile trail that rises some 2,000 feet from the roaring waters of Fires’ Creek to the surrounding ridges under Big Stamp, a former bald where deer and bison had bedded down on the grassy meadow centuries ago. Marshall’s description of the Cherokee trail seems accurate. This does go unerringly in a straight uphill line, unlike the switchbacks of later trails constructed for modern hikers. Cherokee trails were hated by the American armies who penetrated into their mountain kingdom. Their trails go straight up and down the mountains at perilous inclines that make horses balk and hauling wagons impossible. These were the fastest routes to the ridgetops before dropping down to the river towns where the Cherokee raised their children, grew their corn and danced in the ceremonies. This trail would likely have been a route over the ridges between the river towns of Tusquitte near modern-day Hayesville over to Tomatly, just north of Andrews. At half a mile, I’ve climbed about 800 feet, according to the GPS on my watch. The satellites orbiting hundreds of miles overhead watching me like an ant crawl up the mountainside. The trail itself tends to disappear in the leaf litter, a bare hint or suggestion running across roots and rocks. But this ancient route has been maintained. Blue blazes dot the trees above, rectangular plastic strips nailed to the trees every 50 feet or so, and crews have come through with chainsaws, clearing deadfall of previous winters. I follow my own spirit guides, my hiking companions today – Ben my faithful Golden Retriever and a new recruit Merlin, a rescue Poodle who’s about a year and half. Merlin stays by Ben’s side as they travel, Ben stopping ahead to make sure I’m not getting lost as I catch my breath. Ben stops to wallow in the dust, picking up a blazon on his right shoulder of some funky green shit, an irresistible spoor. There are signs of other animals who have followed this same path, scat - long ropy droppings of predators who’ve feasted on white and dark furred prey. Perhaps bear, maybe coyote. Another good sign. The Cherokee like indigenous people worldwide probably followed game trails. As I scramble uphill with labored breath and aching calves, the surrounding mountains come into view through the bare winter woods. At my back there is Brasstown Bald, down in Georgia, and I get glimpses of Lake Chatuge, the impoundment of the Hiwassee River, which flooded out old towns of the Cherokee and the white settlers who came later. There are no signs of civilization other than that diverted water. A jet drives unseen overhead, screeching across the sky, probably on a direct flight path out of Hartsville International 100 miles southwest in Atlanta. It is hard to escape our time and technology. The mountains keep their ancient shape, but the woods would have been different. The old-growth forests were clear-cut a century ago. And the chestnuts that made up a huge part of the hardwood died out with a blight brought from China. The younger growth is scragglier with more underbrush. There are blackened stumps and scorched trunks, signs of the massive wildfires that swept the Nantahalas during a fierce drought two years ago, another red-warning signal of the climate change that is reshaping our hospitable planet. Every landscape spells its own loss. The Cherokee of course were tragically uprooted from their homeland nearly two hundred years ago and forced to march west to Oklahoma along the Trail of Tears in one of our history’s darkest chapters. A few hardy survivors refused the journey, hiding out in the remote coves. These families would become the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Traces of the Cherokee remain, their language merged with the landscape. Any map shows place names from the Cherokee or Tsalagi language: Watauga, Cowee, Cullasaja, Wayah Cartoogechaye, Hiwassee, Nantahala, the list goes on. I have a handful of Cherokee words I’ve learned, though I can’t really follow any fluent speaker. The language itself is more concrete and specific than English, with syntax placing us in time and space before settling on the individual speaker. I’ve learned from a native speaker Bullet Standingdeer who theorizes that the Tsalagi syllables and their piled-up order tell the listener where to physically look. Instead of placing the ego as subject first in your sentence, it’s a different way of walking through a welcoming world, Nogwo usdi nvnohi gega. Now the small road walking am I. Maybe I’ve been walking backwards in landscape in my language, the Cherokee offer a different worldview. After an hour and half, I step out of my meditative trance and into another century. The footpath is swallowed in the intersection with a former logging road, deeply and recently rutted with tire tracks of a heavy-duty four-wheel drive pickup, maybe bear hunters out scouting next year’s hunt. The ghosts are gone. They passed this way, but their footpath has disappeared. Likely they would have kept going over Big Stamp, headed down to the Nantahala River and the town of Tomatly maybe 10 miles below. My dogs splash happily ahead through the muck but wait for me ahead at an old campfire where hikers stopped on the 20 miles Rim Trail that circles the ridges above Fire’s Creek. I eat my turkey sandwich I packed this morning, saving the last bites for both Merlin and Ben, who’s wallowing in more mud and shit. They will need baths later when we get home. The rain that has held off starts a faint sprinkle. It’s time to go. Back home, I’ll download the GPS data from my watch via Bluetooth to my iPhone. The satellite imagery will show my red line like ant trail ending up through the green ridge, the imaginary colors of the map in a winter world showing a palate of grays and browns in reality. 4 hours , 2200 feet, the data shows. But now the trail travels into my muscle memory. I have taken the experience into my brain and bones. I can feel the earth beneath my feet, leaning into the rise, my hiking pole balancing me coming down through the trees, the mountains rolling away to the horizon all around, breathing in the place I feel most at home, outside of time and technology. Nogwo usdi nunohi gega. Now the small trail walking am I.

9 Comments

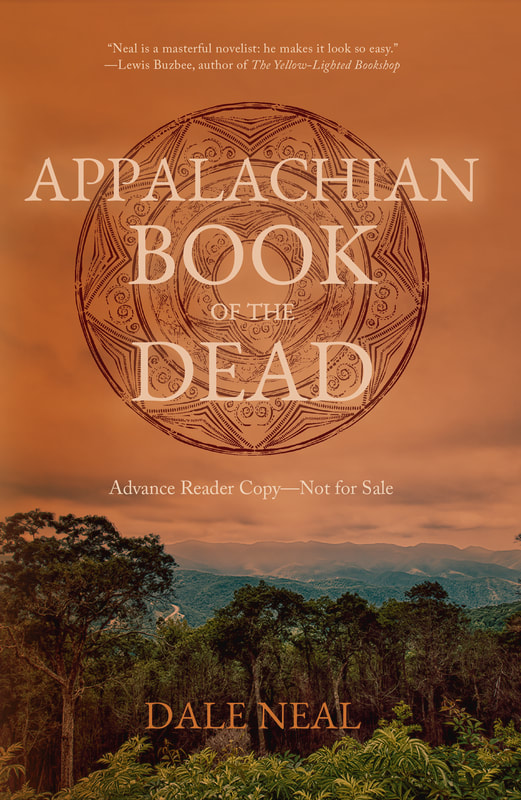

Italo Calvino dives into a good book. Call me old-fashioned or just plain stubborn. I’ve made my living as a journalist for the past thirty years in an industry everybody keeps insisting is in its death throes. And just for fun and my own sanity, I spend my other waking hours, working words into novels, that other mode that people keep saying is dead in our Internet Age. I still believe in books as in physical folios of pages between covers, hard or soft, and not just pixels of an e-book on your new gadget from Amazon or Apple. I still believe in bookstores, independently owned, with their walls and shelves full of brand new books just beckoning to be opened and read. It’s a great joy to have a new book to add to that stock of imagination that independent bookstores traffic in, and to go and meet like-minded people who love to read. I’m excited that the book tour for “Half-Life of Home” is taking shape, thanks to my hard-working publicist Bridgette Lacy. We’ve lined up readings at a few independent bookstores across the state, and more are on the way. So mark these on your calendar and plan to come on out if you have a chance: Malaprop's, Asheville, 7 pm April 13 City Lights, Sylva, 6:30 pm, April 19 Accent on Books, 3 pm, April 27 McIntyres, Pittsboro, 11 am May 4 Blue Ridge Bookfest, Blue Ridge Community College, Flat Rock, May 18  Styron as young literary lion You can’t count me as any kind of Pollyanna. Give me a few overcast days in midwinter, a riff of Miles’s horn on the radio, and I’ll turn blue with the best of them. But melancholy can be a pose, a romantic notion that the tragic is always more interesting than the comic, the mistake too many younger and serious writers tend to make. I’ve been mulling over melancholia lately while reading William Styron. With the recent arrival of Styron’s Selected Letters, I’ve been re-reading his 1951 debut “Lie Down in Darkness” – a bestseller that propelled the 25-year-old writer into instant celebrity. Soon he was padding around the literary lion’s den with the likes of Mailer and James Jones and other red-blooded he-men writers of the Great American Novel. Styron eschewed what he called the “Hemingway mumble school,” tending more toward the purplish expanses of his fellow Southerner Thomas Wolfe. “When I mature and broaden, I expect to use language on as exalted and elevated a level as I can,” the young Styron wrote his Duke mentor William Blackburn. "I believe that a writer should accommodate language to his own peculiar personality and mine wants to use great words, evocative words, when the situation demands them.” I hadn’t read Styron’s novel in 35 years, not since I breezed through as a junior in a contemporary American Lit survey in college. In my bifocaled hindsight now, Styron’s book reads like a young man’s overly romantic vision, not of the Good Life, but of the Marriage Gone Bad – the sorry saga of the alcoholic lawyer Milton Loftis, his estranged Southern belle of a wife, Helen, and their two daughters, the impetuous Peyton, and the special needs daughter, Maudie. The novel charts a single day in August, 1945, just weeks after the bomb feel on Hiroshima. Peyton has committed suicide in New York, and her body had been borne back by train to to the fictional Port Warwick in Tidewater Virginia. Over seven sections and 400 pages in my water-damaged Signet paperback, the book follows Loftis and Helen’s separate journeys to the cemetery, and through their back story of their sad marriage. The opening is masterful, putting “you” into the steamy Southern landscape as the train pulls into the fictional Port Warwick. Throughout, Stryon has a muscular omniscient point of view that can see a fly land on a fat man’s face or how female golfers have to tug at cinching panties, an authoritative voice we don’t hear too often in our more ironic times with the nebbish narratives that have followed after David Foster Wallace. Stryon labored mightily over the book, complaining in his letters how agonizingly slow he found writing. Unfortunately, it shows in the books, which becomes a long march through gloom, leavened by very little humor. There’s a reason that Shakespeare has a jester in King Lear, for a little comic relief and to add to the absurdity. Styron’s idea of comedy is sarcastic, picking on the wide-eyed Negro stereotypes of the time. In the Jim Crow era, pre-Civil Rights South before airconditioning and television, Styron unveils a benighted look at the prevailing racist attitudes. It’s not pretty to read. But it’s still a young man’s notion of tragedy that turns his book into melodrama, the scenes slow to the pace of sticky molasses. There’s pathetic fallacy aplenty as the landscape echoes the alcoholic mood swings of Loftis or the high strung neuroses of Helen, and too often, Styron’s swagger wades too deep into the purplish patches that tripped up Thomas Wolfe. In the end, I had to lay down “Lie Down in Darkness.” I don’t think too many readers will be taking that novel up, nor his “Confessions of Nat Turner” or even “Sophie’s Choice.” Styron himself admitted that his latter fame probably depended more on his slender memoir, “Darkness Visible” about his courageous battle against a debilitating chronic depression, than on his fatter, darker fictions. Styron reads now like a boy whistling in the dark, trying to keep his spirits up, but afraid to truly play. I’m not arguing for sweetness and light, but that a maturer vision sees how to balance the light and the dark in any artful composition. I hold to what one of my teachers, Allan Gurganus, always insisted on: that humor and horror must go hand in hand, hopefully, in a single sentence. Mac McIlvoy suggested in one of his topnotch workshops that writers have to learn to “play in the dark.”  James Dickey, author and actor Faulkner was talking of the South of course when he wrote “the past is not dead, it’s not even past.” Hell, the dead don’t stay buried in these parts, not even if you try to drown them. I was reminded of that the other night, flicking through the HD hinterlands of TV cable when I came across John Boormann’s 1972 thriller “Deliverance.” Even if you never saw the Burt Reynolds-Jon Voight movie, you’ve heard the iconic soundtrack music, “Dueling Banjos” originally written by Arthur Smith (though he had to sue to get his name recognized, but that’s a whole ‘nother tale.) Poet turned novelist James Dickey did no favors to Appalachian natives in his bestseller with its depiction of “the Country of Nine-Fingered Men,” a dark land of sadistic hillbillies eager to sodomize Atlanta suburbanites out for a weekend adventure. Dickey tapped into a deep distrust and terror of residents living in the shadows of mountains. The Other is the toothless man living in the holler with an outhouse and a still up on the ridge. Decades after that movie was filmed in Rabun County, Ga., and over in Sylva, N.C. you still see the bumper stickers “Paddle faster, I hear banjo music.” But the scene that lingered for me showed graves being dug up on the banks of the river slowly flooding to form a reservoir to power Atlanta’s urban sprawl. That scene was actually filmed, not in Georgia, but in South Carolina at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church cemetery which now lies 130 feet beneath Lake Jocasse. We’ve been relocating cemeteries forever in these parts. Folks over in Swain County still grow furious over the “Road to Nowhere” promised by the government, but which never materialized after Lake Fontana flooded their small towns and family farms in the 1940s. The story was repeated across the Southern Appalachians where the TVA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built hundreds of dams, dislocating plenty of families and often covered the graves of their ancestors with waters much more than five fathoms deep. So it comes as no surprise how often floods and forgotten graves show up in Southern fiction. The theme runs like a dark current through the reigning Appalachian master Ron Rash’s work, from his first novel, “One foot in Eden” and “Saints by the River” also based around Lake Jocasse in South Carolina, and in his current novel, “The Cove” where a TVA surveyor goes missing in a haunted holler slated for a lake. Those lakes were built to provide electricity to growing cities and their suburbs whether in Charlotte or Greenville, S.C., or down to Atlanta, but the progress of rural electrification or air conditioning never comes without its own cost when we drown the last wilderness and pieces of our past. An image of a relocated cemetery haunted my imagination and inspired me to write my novel “The Half-Life of Home,” I saw in my mind’s eye a picture of men digging up a graveyard, coffins swinging up into the air in an artificial resurrection. The thirst for electricity, for suburban power was the culprit here, but not in hydroelectric dam, but in a nuclear repository. Since dams sprang up across the South, we’ve also added the strange cones and domes of nuclear plants across the region, with their irradiating wastes with deadly half-lives spanning millennia. A remote cove in my neck of the woods actually came under consideration in the late 1980s as a potential radioactive reservation where East Coast’s stores of spent nuclear rods could be buried for ten thousand years. As a cub reporter I covered those heated public meetings where I heard a white-haired native warn that the region had already seen two forced migrations: the Trail of Tears and the TVA removals. The feds would be chasing other folks off their homesteads in the name once again of national progress. Fortunately, that mad scientist-hatched idea died. We still have nuclear waste to contend with, but at least we’re not burying it in my backyard. Yet the seed was planted in my imagination. Men in moon suits digging up generations of graves. What if… what if? Jesus said let the dead bury the dead, but it seems like the Southern writer’s morbid duty or at least his inclination is to keep pawing away at what’s been covered over, conveniently forgotten. We can’t let the bones rest, the skeletons in the closet. We are always like Hamlet hopping down in the hole, eyeing Yorick’s skull raised in our palm for the audience’s appreciation. And in that sense, Faulkner was right. We breathe life into the past, put flesh on fossils, when we blow away the dirt of the grave or dive deep into the dark waters covering the beds of lakes and forgotten farms. Literature is too often about seemingly unbearable loss, but writing is a way of making sure nothing is ever forgotten. Happy New Year! No hangover this morning. The collards are on the stove along with the hopping john for good luck. The football is about to begin along with a new calendar, counting off the handful of days until my novel is officially out.

I was honored when my pal Nan Cuba, author of the fine upcoming novel BODY AND BREAD invited me to join a blog chain THE NEXT BIG THING - a series of self-interviews by/with authors about what they’ve been working on. Thanks, Nan, and I’m looking forward to seeing your novel coming this May. So here’s what happened when I sat down with myself and asked a few probing questions to which I fortunately knew the answers: Question: Let’s start with the obvious. What’s the name of your book? Answer: THE HALF-LIFE OF HOME Q: Can you give me the one-sentence synopsis? A: Finding your family or losing the land: Royce Wilder, a real estate appraiser, and Kyle McRae, a homeless man, face those hard choices in unearthing long-buried secrets in the mountain community of Beaverdam, N.C. Q: Sounds intriguing. Where did the idea for the book come from? A: I had an image in mind that haunted me. Men in white spacesuits moving across a mountain. They were workers in HazMat suits shielded against radioactive materials, excavating a cemetery on a hillside, digging up the graves of long lost generations, removing them from their land. I had to write a book to find out what happened. Q: What genre does your book fall under? A: Literary fiction with a contemporary Southern Appalachian setting, but the book should appeal to any reader who likes a well-made story about ordinary folk facing extraordinary challenges. Q: What inspired you to write this book? A: Place is character in fiction, I had the good fortune to once hear Eudora Welty say that during a reading in Asheville, and that’s proven true in my own writing. For me, the primal heart of my fiction revolves around the mountain farm my grandparents owned in Watauga County near the N.C.-Tennessee line. The farmhouse and barn and outbuildings, the wooden bridge over the creek, the outcroppings and hemlocks up on the two opposing mountains, the Frozenhead and the Buckeye, all those things spoke to me as a young boy visiting on weekends. That land has since passed out of my family with the death of my grandmother, but it informs my dreams and my fiction. Q: Who’s publishing your book? A: Casperian Books out of Sacramento, Calif., is an independent publisher founded by Lily Richards, who still sees a place for finely crafted fiction in various genres in today’s fragmenting publishing scene. While too many books are being rushed out without oversight, Lily put HALF-LIFE OF HOME through its paces with some great suggestions and a close line-by-line edit. I couldn’t be prouder of the work she put into the production of my second novel. Q: How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript? A: I started this book the day after I graduated from Warren Wilson College with an MFA in creative writing way back in January 1989. After spending so much time focused on writing short stories for workshops and answering to supervisors, I was determined to write a novel all by my lonesome. How lonely it could be I was soon to discover. It probably took me about six months to write a 400-page first draft and I still remember that sense of exhilaration: “I’ve written what looks like a novel.” But that was only the beginning. It took several more drafts before I talked an agent into taking a look around 1992. She sent it back with the suggestion to cut it by 100 pages. I did. She took it on and shopped it around New York. Eighteen houses all told took a pass and the agent cut me loose. I went on and wrote another novel and then a third, “Cow Across America.” Then hiking one day up in the mountains north of Asheville, I came across what needed to be done with that first novel. I can still remember the bend of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail where the Muse suddenly whispered the solution. In the original book, the main character, Royce Wilder came across as an immature man, still acting out against his parents even as a grown man. I decided to split his character into two, a fretting father and an adolescent son in rebellion. Adding 14-year-old Dean changed all the family dynamics and the basic plot line. Perseverance is what I’ve found really matters in a quarter century of making books. If a writer takes care of the writing, the publishing takes care of itself. “Cow Across America” won the Novello Literary Award from the Charlotte Mecklenberg Public Library and was published in 2009. Casperian Books took on “The Half-Life of Home” back in February of last year. The novel officially hits the shelves on April Fools Day (no fooling.) Q: What other books would you compare this story to? A: Wendell Berry’s “A Place on Earth.” Fred Chappell’s marvelous series of novels starting with “I am One of You Forever.” John Ehle’s neglected masterpiece “Last One Home.” Gail Godwin’s “Father Melancholy’s Daughter.” Q: What about a movie? Which actors would you choose to play your characters? A: It’s hard to put faces on characters who seem real but are in the end made up of words on the page. If I were a Hollywood casting director, I’d say Bill Murray possesses the wryness and interior self-doubt to play Royce. Joaquin Phoenix (Anyone see “The Master”?) has the angular angst necessary for the part of the homeless man, Kyle. I can see Allison Janney (remember her from The West Wing?) as Eva, Royce’s unhappy wife. One of my favorite all-time actors Robert Duvall as the aging uncle, Dallas Rominger. And if we’re going big-budget, why not Meryl Streep in makeup as the “witch woman” Wanda McRae. Q: What else about your book might pique the reader's interest? A: Literature is about loss, summoning up a time and a place in words that will last beyond the lifetimes of our loved ones and the places they lived. Mountaineers have been forced off their land since the Cherokees were herded along the Trail of Tears. Homesteaders were forced out by the fed- eral government in the 1930s to make way for hydroelectric dams. After the war, they left their farms to find jobs in Piedmont cotton mills or car factories up north. As a cub reporter in the ’80s, I covered hearings where federal bureaucrats earnestly debated turning remote mountain coves into a national nuclear repository. That image haunted me: what if radioactivity leaking out of these ancient mountains forced people off their land? Read Nan Cuba’s self-interview about BODY AND BREAD here. Passing the baton, I’ve tagged a couple of writers who you should check out: Marjorie Hudson is the author of ACCIDENTAL BIRDS OF THE CAROLINAS, a fine collection of short stories that was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. Michael Jarmer is the author of MONSTER LOVE, a contemporary twist on Mary Shelley Wollenstone’s classic “Frankenstein.” MaryJo Moore is a fine Native American writer and editor living here in Asheville. Her latest volume of wisdom is BEAR QUOTES. You might also be interested in these writers who I know are part of the NEXT BIG THING chain. Joe Schuster, whose book, THE MIGHT HAVE BEEN is a terrific baseball novel with a compelling human story. Christine Hale, an Asheville memoirist and novelist whose guest blog will appear Jan. 5 here: Happy New Year and happy reading in 2013.  The winter solstice seems appropriate a time to be starting a new blog. Tomorrow there's a sliver more daylight as we head into a new year and the launch of my second novel The Half Life of Home, (Coming courtesy of the fine folks at Casperian Books.) But I'm staking out my corner of the cyberspace to let readers know about upcoming events and share some thoughts. Putting a new book out into the world is always a lark and an adventure. At these moments, I go back to one of my favorite writers - James Salter - and his thoughts from his memoir Burning the Days: "When was I happiest, the happiest in my life? Difficult to say. Skipping the obvious, perhaps setting off on a journey, or returning from one. In my thirties, probably, and at scattered other times, among them the weightless days before a book was published and occasionally when writing it. It is only in books that one finds perfection, only in books that it cannot be spoiled. Art, in a sense, is life brought to a standstill, rescued from time The secret of making it is simple: discard everything that is good enough." It's also nice to start a fresh page or a new blog with a bit of good news. The good folks at The New Southerner have just put up an excerpt from the novel The Half-Life of Home as part of their 2012 literary contest. Thanks to Bobbi Buchanan and the final fiction judge Silas House for the honor. Check out the handsome online magazine at www.newsoutherner.com. I'll be in Louisville, Ky, for a reading Jan 12 with the other contest winners. Looking forward to a drive into the Bluegrass State. |

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed