(I'm reposting this blog which first appeared at "Beyond the Margins," thanks to my pal and a very fine writer, Robin Black). Dante Alighieri was deep in the woods, a failed politico exiled from his beloved Florence, flailing through his mid-30s and a mid-life crisis, before he found the way, punching his ticket to hell, purgatory, heaven and of course literary immortality with The Divine Comedy. I, too, was in the woods, an unpublished fiction writer about to turn 45 when I figured out the wrong fork I had taken in my novel more than ten years before. Talk about a slow learner, but I think most novelists fall into that club - quick studies of human foibles who plod through seemingly endless drafts before they arrive at a well-made book. I still remember the day I started writing my first novel. It was a sunny morning in mid-January, 1989. My walking stick leaned by my desk, a souvenir of time served in the workshops of Warren Wilson College where I earned my MFA. I clicked open a new file on my Commodore 12 PC and commenced. I had spent the previous three years, studying and dissecting and attempting to write short stories, which seemed like stepping stones or way stations toward the big novel, which I now felt brave enough or foolhardy enough to undertake. Now, there would be no supervisor, no feared teacher guide, to tell me what I was doing wrong. By late summer, I had typed the last of 400 pages. I still recall that instant of exaltation. I had done it, written a thing that resembled a real novel. Now, just to work through a few drafts, polish up the prose, and I would be on my way to the Big Time. I finally shipped it off to a New York agent around 1992. The manuscript miraculously made it out of the slush pile onto her desk, and she sent it back with the thought, “Cut 100 pages, I’ll take another look.” I was horrified. Writers at first resist. Writers at last do what’s necessary. Henry James once wrote to an editor who requested three lines cut from a 5,000- word article. “I have performed the necessary butchery. Here is the bloody corpse.” I shrugged off the chip on my shoulder and did the deed. Another year and I resent the revised manuscript. She signed me. That should have been the end of the story, where the writer lives happily ever after, or so I thought. The agent sent the book out to eighteen major houses and could not sell it in New York. We parted ways around 1995, and I despaired of ever publishing a book, but I did what writers do: I kept writing. I could feel my life passing me by at the desk. No book to my name out in the world, but to my credit, I kept piling up words and pages and drafts. In 2003, I was hiking the Mountain-to-Sea Trail in the Black Mountains above Asheville. An elevation around 5,000 feet, the forest edging toward the boreal, always does wonders to clear my head. I came across a grove of cedars that never fails to remind me of pencil shavings and Hemingway’s wonderful evocation of the writing life from A Moveable Feast. Hemingway liked writing at the cafe when “some days it went so well that you could make the country so you would walk through it… Even when the pencil broke and you had to stop to sharpen the point again, then slip your arm through the sweat-salted leather of your pack- strap to lift the pack again, get the other arm through and feel the weight settle on your back and feel the pine needles under your moccasins as you started down for the lake.” Stepping into that sun-dappled grove, I met my moment of inspiration, my Muse, or at least realized what was needed to resuscitate that first novel. At age 31, I had tried to imagine a man 10 years older than me and how he would react to the loss of his family farm, putting his aging mother into a nursing home, while suspecting his wife of cheating on him with her spiritual confessor. Royce Wilder was his name, but a decade of hindsight, he seemed whiny and adolescent in his actions, not nearly as grownup as his circumstances demanded. But not to blame Royce, he was perhaps too accurate a projection of the author as a younger man. When I started typing in 1989, I simply lacked the imagination or life experience to know his plight or put it convincingly on the page. My insight on the trail was that I suddenly understood that Royce needed his own adolescent son. In essence, the novel demanded that I clone a single character into two. It took several more drafts before I settled on Dean Wilder, age 14, who’s taken up graffiti and smoking a little dope in his own quest to find himself. Introducing another character changed the whole trajectory of the novel, the plot, the ending, everything. In 2009, I published my “first” novel Cow across America, winner of the Novello Literary Award. That actually was the third book I had written. In April, The Half-Life of Home makes its debut. I’m now a decade older than my main character, and he seems young to me again. It’s been 25 years now since I’ve started my apprentice novel. I’ve come to understand there’s no steady climbing of some career ladder in literature. You go only as high as the stack of pages you pile up in the desk drawers or virtually on hard drives, online reaching to the Cloud. Now nearing my 55th birthday, mathematically well past Dante’s midlife quest, I’m still feeling my way along. In our culture, we always want morals with our stories, a leavening of education with our entertainment. I’m not sure what I’ve really learned about making novels, other than it takes time. But then that’s the beauty of the form itself, a way of watching characters grow and change over fictional years, decades, lifetimes. Writing a novel? It’s a walk in the woods.

1 Comment

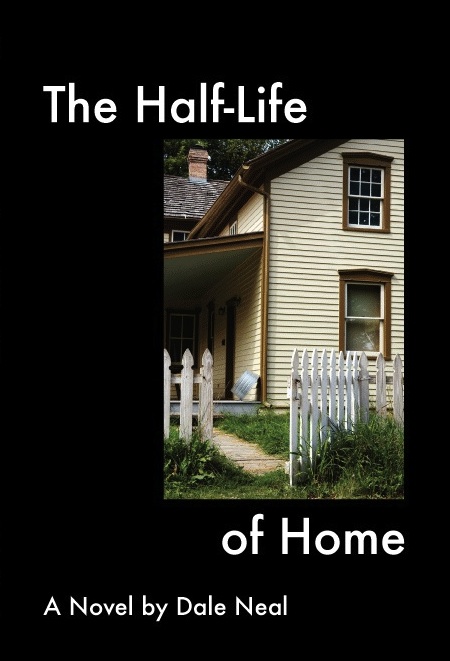

His name was Kenny, a member of the Cherokee tribe who lived out Qualla way and drove into town for a reading by a novelist he didn't know. I saw him flipping through the racks of used books at the back of City Lights and then slip into the back row as my reading began at the appointed hour. I could see his face captivated, and when it was time for questions, he raised his hand. "Where did you get that story about the Shadow Man?"

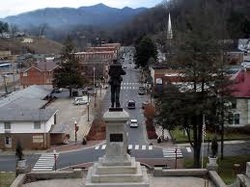

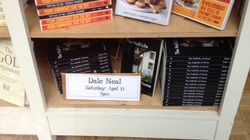

In the novel's opening, Royce hears about the Shadow Man as a young boy, a scary monster who lived in the woods who would steal the shadows of passing Indians, but especially those of little boys. Without their shadows to anchor them to earth, the Indians all blew away in the wind. "I made it up, I believe. I don't think I ever heard anyone mention the Shadow Man." Turns out the Shadow Man is a fixture in Kenny's family. The Cherokee elders talked about a ghost who roamed the ridges, they called the Shadow Man, who trailed after you if you went walking in a certain woods. "Fiction is a force of memory improperly understood," John Cheever once wrote. And sometimes as a writer, you just hit paydirt, uncovering an archetype deep in the primal memory. That's part of the adventure of writing a novel and finding readers who bring their own memories and stories to its re-creation when they read your story. I love getting questions like Kenny's and meeting readers like him, eager to go exploring. My next sto at Accent on Books, my favorite little bookstore in North Asheville, not far from Beaverdam (no, not the one in the novel, but close enough.) I'll be there this Saturday, April 27 starting at 3 p.m. Patrick and Lewis, real bookmen, have been strong supporters of my work and good friends over the years. Accent on Books has a monthly book club as well that will take up "The Half-Life of Home" in May. So I'm psyched to meet more readers ready with their questions.  Scenic downtown Sylva You need to check out Sylva, one of our more scenic small towns here in Western North Carolina, which boasts not only a Confederate statue and an old-timey courthouse on the hill, but one of the best little bookstores around - City Lights Books, where I read from "Half-Life of Home" on a Friday spring evening to an appreciative audience. Thanks Chris and Eon for making me feel at home. Meanwhile, Pam Kelley, who writes the Reading Life column for the Charlotte Observer, observed my new novel nicely in her blog "The Reading Life." It's always strange for a journalist to have the usual roles reversed and be on the receiving end of the inquistion: So what's your novel about? What inspired you to write it? Etc. Pam did a yeoman's work in summarizing the book and picking out the high points of our conversation. Here's Pam's review: A simple, everyday garage sale opens Dale Neal’s new novel, “The Half-Life of Home,” but it’s a garage sale fraught with meaning. Eva Wilder can’t wait to rid herself of the clutter her family has accumulated over two decades. But when her husband, Royce Wilder, eyes the items for sale, he sees memories, not junk. This tug between past and present, and the complicated relationship most of us have with change, lies at the heart of Neal’s story. It’s the second novel for Neal, 54, a reporter for the Asheville Citizen-Times. His first, “Cow Across America,” won the 2009 Novello Literary Award from the Charlotte-Mecklenburg library. “The Half-Life of Home” (Casperian Books; $15.95) takes place in two fictional N.C. mountain towns, Beaverdam and Altamont. (He borrowed “Altamont” from Thomas Wolfe’s “Look Homeward Angel,” where it stands in for Asheville.) Neal sets his story in 1992. The Internet and digital technology haven’t yet transformed the world, but middle-aged Royce Wilder feels his once-secure life shifting beneath his feet. Raised in rural Beaverdam, he has moved to Altamont, a town that is becoming populated by transplants, strangers instead of neighbors. His wife seems distant, his teenaged son, rebellious. And the family is struggling to finance a lifestyle that includes his son’s private-school education. Pressure to sell family land grows when he learns his hometown emits dangerously high levels of radon gas. There’s even talk that the area could become a radioactive waste dump. In Beaverdam, meanwhile, a rash of break-ins prompts suspicion that Wanda McRae, a troubled soul known as the Witch Woman, has been making forays into town from her mountain cabin. Royce discovers the Witch Woman holds a secret about his family. He also learns to move forward. Though more than a few Southern novels mythologize the past (such as “Gone With the Wind”), one message in this book is about letting the past go. Neal recalls a great-uncle who said it was a lot easier to start a car engine than hook up a horse. Sometimes, Neal says, progress can be a wonderful thing. Neal will read twice in Charlotte on May 12 -- at 2 p.m. at Park Road Books, 4139 Park Road, and 4 p.m. at the Wingmaker Arts Collaborative, 207 W. Worthington Ave, where he’ll be joined by fiction writer Kathryn Schwille and poet Gail Peck. Read more here: http://www.readinglifeobs.blogspot.com/#storylink=cpy My new novel "The Half-Life of Home" got quite the homecoming celebration Saturday night at Malaprop's Bookstore & Cafe, with about 40 or so folks drifting in and out to hear me read. I can't express all my gratitude for Malaprop's and what Emoke B'racz and her dedicated staff of bookworms have done over the decades to satisfy my serious jones for the hard lit stuff. I ordered my first copies of Chekhov and Babel here way back in grad school at Warren Wilson, and they've kept me supplied with the good stuff ever since from Roth to DeLillo, Franzen to DFW, Ford to Salter.

So it was a rare privilege to return to the same podium where so many literary lions and lionesses have read before me, and I'm deeply grateful to all the people who came. If you couldn't make to the mountains, never fear. There are stops and bookstores ahead where I'll be reading from "The Half-Life of Home." April and May are shaping up as busy months on the book tour, as nice reviews for "The Half-Life of Home" start to roll in from newspapers and the first readers.

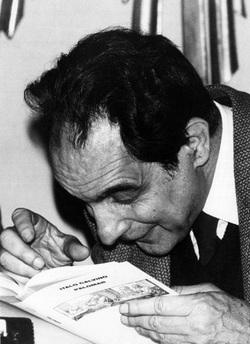

Rob Neufeld of the Asheville Citizen-Times had kind words for my book in Sunday's review: "The family’s place at the center of the “Half-Life” universe is one of the novel’s beauties. There’s a perfect balance within its structure: the middle-class unit under great pressure at the center; the Appalachian past tugging, with its history of displacement, poverty and folkloric horror; the Appalachian present pushing, with real estate imperatives; and the no-borders world of current media drawing Royce’s teenage son, Dean, into its disaffection." And my old pal Lewis Buzbee had this to say on GoodReads: "Like the best novels, this is the story of the past colliding with the future, where the characters struggle to find some order in the inevitable chaos of change. If you love a good novel, you need this book. "The story is set in the deep woods of North Carolina, where the land, poisoned by those who've owned it, now threatens every one that's been left behind. But the land will prevail, as it always does. Along the way, readers will meet an unforgettable cast of characters, from Witch Woman to Snakebit Girl, and those modern demons, businessmen. This isn't just a great Southern novel, but a great American novel. And the writing, well, it's pitch perfect and absolutely seductive. You won't put it down; you won't forget it." And do come on out for a reading. I would love to see you: Malaprop's, Asheville, 7 pm April 13 City Lights, Sylva, 6:30 pm, April 19 Accent on Books, 3 pm, April 27 Quail Ridge, Raleigh, 7 pm May 3 McIntyres, Pittsboro, 11 am May 4 Park Road Books, Charlotte, 2 pm. May 12 Pomegranate Books, Wilmington, 7 pm May 21 Blue Ridge Bookfest, Blue Ridge Community College, Flat Rock, May 18  I am a believer, in books at least. For me, fiction makes the world real. James Salter may have said it best when he was asked why : "To write? Because all of this is going to vanish. The only thing left will be the prose and the poems, the books, what is written down. Man is very fortunate to have invented the book." After years of writing and revising, piling up manuscript drafts, and yes, lots of rejection, it is a wonder when you finally see the book you've spent half a lifetime imagining and bringing to life, that very book stacked so nicely in the window of your neighborhood bookstore - in this case, Malaprop's in downtown Asheville. For all the folks who can't drive to Asheville, you can also order "The Half-Life of Home" from my Sacramento publisher, Casperian Books, for a rather nice price. Order your copy here.  Italo Calvino dives into a good book. Call me old-fashioned or just plain stubborn. I’ve made my living as a journalist for the past thirty years in an industry everybody keeps insisting is in its death throes. And just for fun and my own sanity, I spend my other waking hours, working words into novels, that other mode that people keep saying is dead in our Internet Age. I still believe in books as in physical folios of pages between covers, hard or soft, and not just pixels of an e-book on your new gadget from Amazon or Apple. I still believe in bookstores, independently owned, with their walls and shelves full of brand new books just beckoning to be opened and read. It’s a great joy to have a new book to add to that stock of imagination that independent bookstores traffic in, and to go and meet like-minded people who love to read. I’m excited that the book tour for “Half-Life of Home” is taking shape, thanks to my hard-working publicist Bridgette Lacy. We’ve lined up readings at a few independent bookstores across the state, and more are on the way. So mark these on your calendar and plan to come on out if you have a chance: Malaprop's, Asheville, 7 pm April 13 City Lights, Sylva, 6:30 pm, April 19 Accent on Books, 3 pm, April 27 McIntyres, Pittsboro, 11 am May 4 Blue Ridge Bookfest, Blue Ridge Community College, Flat Rock, May 18 I spent most of the weekend with a new tripod, a mic and a stablizer for the iPhone that I checked out from work, practicing my video-making skills and spinning out my thoughts about the new book. We're making a bigger push as visual storytellers at the Asheville Citizen-Times and newspapers nationwide, trying to keep print journalism relevant in the world that Steve Jobs made with iPhones and iPads and other nifty devices.

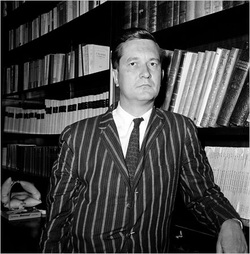

The same pressures bearing down on the journalism industry are of course revealing cracks and crevasses in the publishing industry and how we buy and read books. After you spend years and even decades on a piece of fiction, I still find it fun to go back and remember those first images that triggered that avalanche of words, the seemingly endless drafts, and the long round of edits to bring a book into the world. "The Half-Life of Home" makes its official debut on April 1, fittingly April Fool's Day. I won't say that writing a novel is a fool's errand in the 21st century with our culture's attention deficit disorder, but it helps to have a sense of humor and perspective. As I say in the video (to myself and the camera's eye), I didn't come from a long line of garrulous storytellers eager to spill all the beans and family secrets to an impressionable child. I grew up in a protective silence, with all the juiciest stories going on just out of earshot, for adults only after I had gone outside to play or been sent off to bed. But in that silence, the seeds of the imagination were planted. Growing up, I had to fill in the blanks, to imagine what I didn't know for a fact, feeling in the dark for what is unseen. I think that's why I was so ripe at age 15 when I discovered the novels of Thomas Wolfe, who wrote about "the buried life," what it was like to grow up in a provincial, hillbound town like Asheville, NC, about a century before Asheville became such a cool little burg for hipsters and the creative class. Wolfe knew something about breaking out of silence, even if it was charging headlong into overwritten purple patches at times in his novel. But reading Wolfe, I knew for the first time that, yes, I wanted to do what he had done, to write a book that told the truth about what he felt and saw in this strange, amazing life we share on this planet. I didn't realize it would take me another 35 years before I would publish that first book, but the time spent with all those words was worth it.  Styron as young literary lion You can’t count me as any kind of Pollyanna. Give me a few overcast days in midwinter, a riff of Miles’s horn on the radio, and I’ll turn blue with the best of them. But melancholy can be a pose, a romantic notion that the tragic is always more interesting than the comic, the mistake too many younger and serious writers tend to make. I’ve been mulling over melancholia lately while reading William Styron. With the recent arrival of Styron’s Selected Letters, I’ve been re-reading his 1951 debut “Lie Down in Darkness” – a bestseller that propelled the 25-year-old writer into instant celebrity. Soon he was padding around the literary lion’s den with the likes of Mailer and James Jones and other red-blooded he-men writers of the Great American Novel. Styron eschewed what he called the “Hemingway mumble school,” tending more toward the purplish expanses of his fellow Southerner Thomas Wolfe. “When I mature and broaden, I expect to use language on as exalted and elevated a level as I can,” the young Styron wrote his Duke mentor William Blackburn. "I believe that a writer should accommodate language to his own peculiar personality and mine wants to use great words, evocative words, when the situation demands them.” I hadn’t read Styron’s novel in 35 years, not since I breezed through as a junior in a contemporary American Lit survey in college. In my bifocaled hindsight now, Styron’s book reads like a young man’s overly romantic vision, not of the Good Life, but of the Marriage Gone Bad – the sorry saga of the alcoholic lawyer Milton Loftis, his estranged Southern belle of a wife, Helen, and their two daughters, the impetuous Peyton, and the special needs daughter, Maudie. The novel charts a single day in August, 1945, just weeks after the bomb feel on Hiroshima. Peyton has committed suicide in New York, and her body had been borne back by train to to the fictional Port Warwick in Tidewater Virginia. Over seven sections and 400 pages in my water-damaged Signet paperback, the book follows Loftis and Helen’s separate journeys to the cemetery, and through their back story of their sad marriage. The opening is masterful, putting “you” into the steamy Southern landscape as the train pulls into the fictional Port Warwick. Throughout, Stryon has a muscular omniscient point of view that can see a fly land on a fat man’s face or how female golfers have to tug at cinching panties, an authoritative voice we don’t hear too often in our more ironic times with the nebbish narratives that have followed after David Foster Wallace. Stryon labored mightily over the book, complaining in his letters how agonizingly slow he found writing. Unfortunately, it shows in the books, which becomes a long march through gloom, leavened by very little humor. There’s a reason that Shakespeare has a jester in King Lear, for a little comic relief and to add to the absurdity. Styron’s idea of comedy is sarcastic, picking on the wide-eyed Negro stereotypes of the time. In the Jim Crow era, pre-Civil Rights South before airconditioning and television, Styron unveils a benighted look at the prevailing racist attitudes. It’s not pretty to read. But it’s still a young man’s notion of tragedy that turns his book into melodrama, the scenes slow to the pace of sticky molasses. There’s pathetic fallacy aplenty as the landscape echoes the alcoholic mood swings of Loftis or the high strung neuroses of Helen, and too often, Styron’s swagger wades too deep into the purplish patches that tripped up Thomas Wolfe. In the end, I had to lay down “Lie Down in Darkness.” I don’t think too many readers will be taking that novel up, nor his “Confessions of Nat Turner” or even “Sophie’s Choice.” Styron himself admitted that his latter fame probably depended more on his slender memoir, “Darkness Visible” about his courageous battle against a debilitating chronic depression, than on his fatter, darker fictions. Styron reads now like a boy whistling in the dark, trying to keep his spirits up, but afraid to truly play. I’m not arguing for sweetness and light, but that a maturer vision sees how to balance the light and the dark in any artful composition. I hold to what one of my teachers, Allan Gurganus, always insisted on: that humor and horror must go hand in hand, hopefully, in a single sentence. Mac McIlvoy suggested in one of his topnotch workshops that writers have to learn to “play in the dark.”  James Dickey, author and actor Faulkner was talking of the South of course when he wrote “the past is not dead, it’s not even past.” Hell, the dead don’t stay buried in these parts, not even if you try to drown them. I was reminded of that the other night, flicking through the HD hinterlands of TV cable when I came across John Boormann’s 1972 thriller “Deliverance.” Even if you never saw the Burt Reynolds-Jon Voight movie, you’ve heard the iconic soundtrack music, “Dueling Banjos” originally written by Arthur Smith (though he had to sue to get his name recognized, but that’s a whole ‘nother tale.) Poet turned novelist James Dickey did no favors to Appalachian natives in his bestseller with its depiction of “the Country of Nine-Fingered Men,” a dark land of sadistic hillbillies eager to sodomize Atlanta suburbanites out for a weekend adventure. Dickey tapped into a deep distrust and terror of residents living in the shadows of mountains. The Other is the toothless man living in the holler with an outhouse and a still up on the ridge. Decades after that movie was filmed in Rabun County, Ga., and over in Sylva, N.C. you still see the bumper stickers “Paddle faster, I hear banjo music.” But the scene that lingered for me showed graves being dug up on the banks of the river slowly flooding to form a reservoir to power Atlanta’s urban sprawl. That scene was actually filmed, not in Georgia, but in South Carolina at the Mount Carmel Baptist Church cemetery which now lies 130 feet beneath Lake Jocasse. We’ve been relocating cemeteries forever in these parts. Folks over in Swain County still grow furious over the “Road to Nowhere” promised by the government, but which never materialized after Lake Fontana flooded their small towns and family farms in the 1940s. The story was repeated across the Southern Appalachians where the TVA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built hundreds of dams, dislocating plenty of families and often covered the graves of their ancestors with waters much more than five fathoms deep. So it comes as no surprise how often floods and forgotten graves show up in Southern fiction. The theme runs like a dark current through the reigning Appalachian master Ron Rash’s work, from his first novel, “One foot in Eden” and “Saints by the River” also based around Lake Jocasse in South Carolina, and in his current novel, “The Cove” where a TVA surveyor goes missing in a haunted holler slated for a lake. Those lakes were built to provide electricity to growing cities and their suburbs whether in Charlotte or Greenville, S.C., or down to Atlanta, but the progress of rural electrification or air conditioning never comes without its own cost when we drown the last wilderness and pieces of our past. An image of a relocated cemetery haunted my imagination and inspired me to write my novel “The Half-Life of Home,” I saw in my mind’s eye a picture of men digging up a graveyard, coffins swinging up into the air in an artificial resurrection. The thirst for electricity, for suburban power was the culprit here, but not in hydroelectric dam, but in a nuclear repository. Since dams sprang up across the South, we’ve also added the strange cones and domes of nuclear plants across the region, with their irradiating wastes with deadly half-lives spanning millennia. A remote cove in my neck of the woods actually came under consideration in the late 1980s as a potential radioactive reservation where East Coast’s stores of spent nuclear rods could be buried for ten thousand years. As a cub reporter I covered those heated public meetings where I heard a white-haired native warn that the region had already seen two forced migrations: the Trail of Tears and the TVA removals. The feds would be chasing other folks off their homesteads in the name once again of national progress. Fortunately, that mad scientist-hatched idea died. We still have nuclear waste to contend with, but at least we’re not burying it in my backyard. Yet the seed was planted in my imagination. Men in moon suits digging up generations of graves. What if… what if? Jesus said let the dead bury the dead, but it seems like the Southern writer’s morbid duty or at least his inclination is to keep pawing away at what’s been covered over, conveniently forgotten. We can’t let the bones rest, the skeletons in the closet. We are always like Hamlet hopping down in the hole, eyeing Yorick’s skull raised in our palm for the audience’s appreciation. And in that sense, Faulkner was right. We breathe life into the past, put flesh on fossils, when we blow away the dirt of the grave or dive deep into the dark waters covering the beds of lakes and forgotten farms. Literature is too often about seemingly unbearable loss, but writing is a way of making sure nothing is ever forgotten. |

Dale NealNovelist, journalist, aficionado of all things Appalachian. Archives

April 2023

Categories

All

|

|

© Dale Neal 2012. All rights reserved.

|

Asheville NC Contact

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed